by Richard Seltzer, seltzer@seltzerbooks.com,

from DECWORLD the company newspaper, March 1983

No one would expect a new and relatively

small computer company to mount a major effort to sell its

latest and most complex system on the other side of the world.

But in 1964, DEC, with about $10 million in annual sales,

pursued an opportunity for a multi-million dollar sale of

several PDP-6 computers in Australia. It succeeded in selling

one PDP-6 in Perth -- as far away from Maynard, Massachusetts,

as it is possible to go without leaving the Earth. From that

beginning, through the efforts of a handful of experienced

pioneers, DEC's business spread through the Far East, Latin

America and Africa, becoming a vast worldwide enterprise.

The prologue to this story started six years

earlier, when Gordon Bell, a student in electrical engineering

at MIT, went to Gordon Bell, a student in electrical engineering

at MIT, went to the University of New South Sales in Sydney,

Australia, as a Fulbright scholar. There he worked for Ron Smart

in the computer lab.

The university had just been started in 1949,

and Ron, studying electrical engineering, was in the second

graduating class. shortly

after graduation, the university had hired him and sent him to

England to purchase their first computer. Then he returned to

Australia and set up the computer center, running it as a

business that serviced the university an private industry. It

was a "DEUCE:" computer. Computer pioneer Alan Turing had been

involved in its design. (There's a piece of a DEUCE in the

Computer Museum now.)

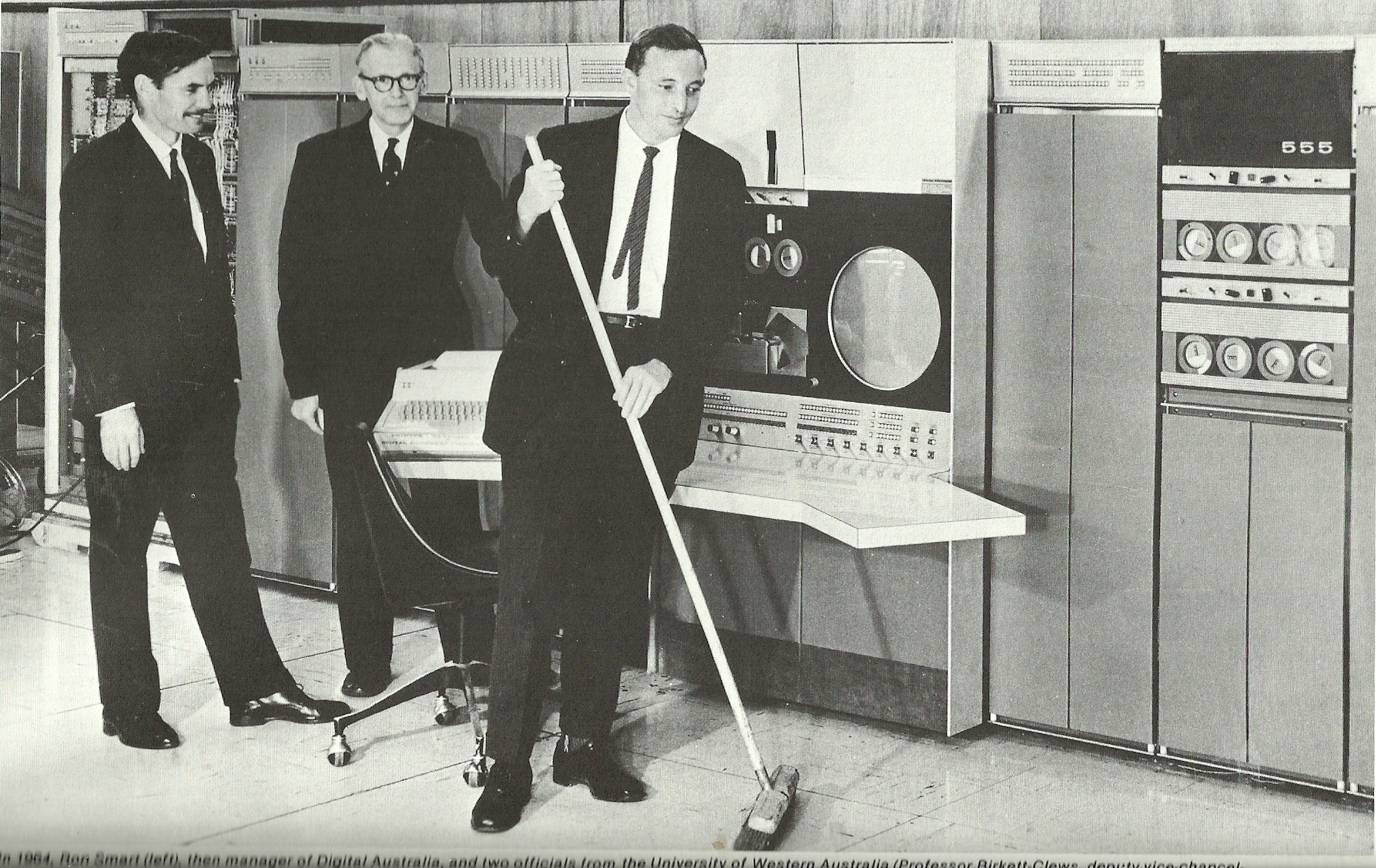

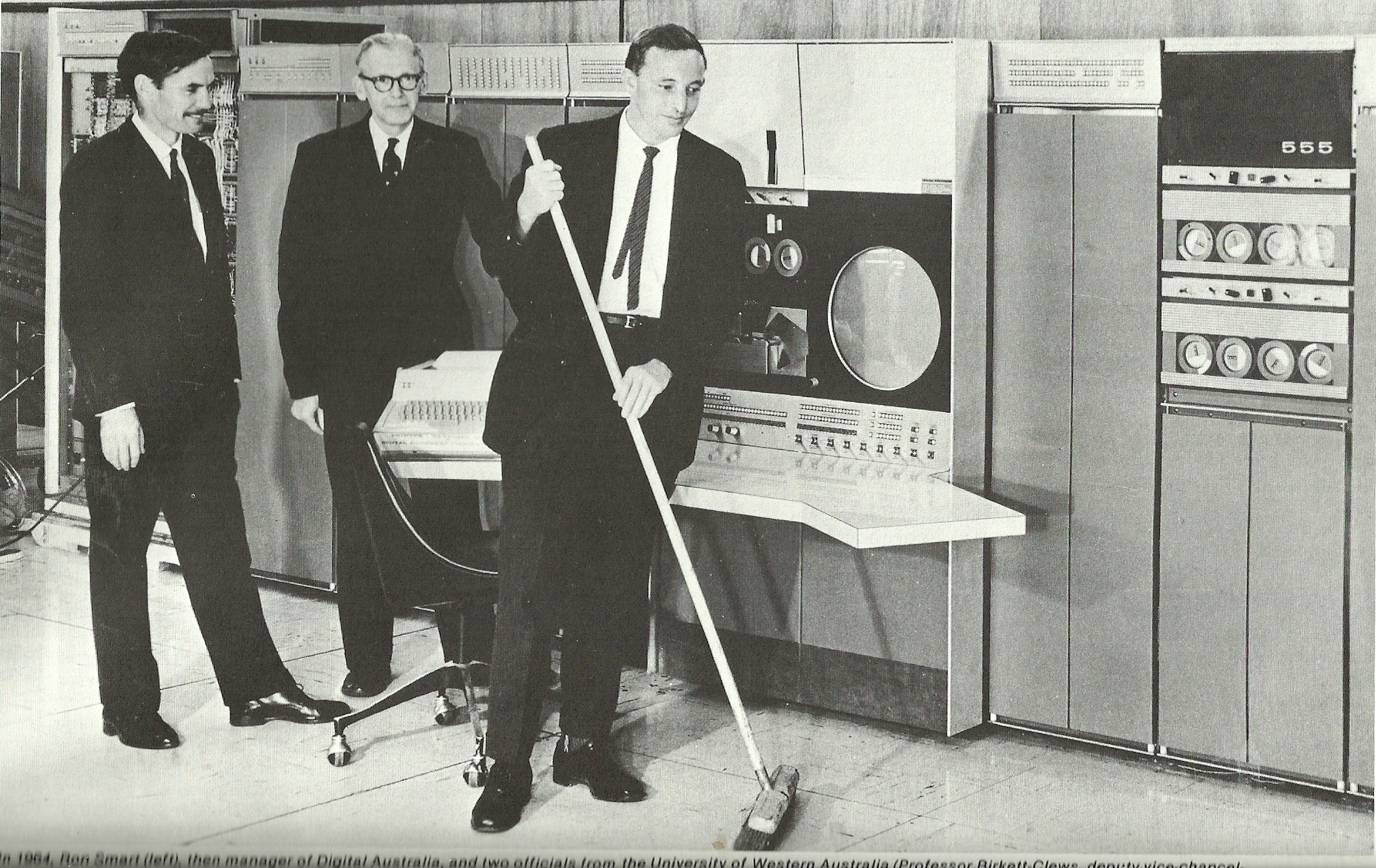

In

1964, Ron Smart (left), then manager of Digital Australia, and

two officials from the Universiy of Western Australia

(Professor Birkett-Clews, deputy vice-chancellor, and D.W.G.

Moore, director of the Computing Center) came to Maynard for a

demonstration of the recently introduced PDP-6 computer

system.

In those early days, the university was

modelling itself after MIT, and a number of personal contacts

had been made between the two institutions. Those ties were

probably behind the suggestion that Gordon go to this

university.

After Gordon returned to Boston, he joined

DEC, then a fledgling company with about a hundred employees.

(His is now vice president, Engineering.) Then in 1964, when he

returned to Australia looking for someone to set up and manage

DEC's sales and service operations there, he offered Ron Smart

the job.

"DEC was attractive to me because it was the

only company where I could continue to work on hardware as well

as on software, and where I could help design system with

modules," Ron recalls. "Furthermore, I was interested in

real-time on-line scientific applications that were only

possible with DEC's products.

The original idea was that I would manage the

operation technically and from a business point of view and hire

somebody else to do the selling.

But it turned out that the business wasn't big enough to

afford an increase in staff.

So to begin with, Digital Equipment Australia consisted

of me and a secretary. We worked out of a spare room in the new

house I had just built in Turramurra, about seven miles outside

of Sydney. I didn't yet have a telephone. I had a call from a

public phone at the corner. It took a lot of sixpences to reach

Maynard."

At the time Ron went to work for DEC, several

people like Harlan Anderson (one of the three founders of

Digital), Gordon Bell, Alan Kotok and Bob Lane had already

visited Australia at different times, working on a proposal for

the sale of PDP-6s to several Australian universities. When Ron

came on board, he continued that effort.

"We sold a time-sharing PDP-6 to the

University of Western Australia in Perth," says Ron. That was

the first timesharing anywhere in Australia. The computer ran

for ten years until being upgraded to a dECsystem-10 in 1974.

Two cabinets from it are still on display in the Wireless Hill

Telecommunications Museum, Melville, Western Australia, and

other parts in the Digital Museum, Sydney.

"The market in Australia was sophisticated

enough to appreciate that kind of machine. Their sophistication,

even today, is born of necessity -- They are so far away from

suppliers that they have to learn to do things themselves. DEC's

approach -- providing general purpose computer tools and putting

computing power int he hands of users -- matched the

Australians' typical drive for independence and self-reliance.

They are attracted to new ideas and are willing to put in the

effort to make them work. So, in many ways, our company and its

products are very well suited to the attitudes that are

prevalent in Australia."

In those days, the job of a sales manager was

highly technical, and the further you went from Maynard, the

more technical you had to be because you had to solve your own

problems. DECUS proceedings included everything scientists were

doing in minicomputers," Ron recalls. "Many of my potential

customers didn't even know what a minicomputer was; so I was

able to show them what they could do with computers and circuit

modules using the DECUS articles from other parts of the world.

"We didn't sell much the first two years,"

explains Ron. "It was a time for seeding future sales."

When he got a PDP-5 demonstration machine in

August 1964, instead of setting it up in his office, he loaned

it to the Electrical Engineering Department at his old

university. It was connected to actual experiments; so potential

customers could see the machine running real-time processing.

Months later, when the University purchased its fist PDP-8, the

PDP-5 was sold to the BHP Research laboratories in Newcastle.

That machine was returned to DEC in 1979 for display in the

company's computer museum at Chatswood as the first minicomputer

in Australia.

People form remote areas were often sent to

Massachusetts for months or even a

year of on-the-job training. The selling styles they

observed during this "training" often differed considerably from

what they were accustomed to back home. For example, Ron

recalls that in 1970 when Australian Max Burnet spent a year

working in the Boston district, he found a huge difference in

the way selling was done. Local sales people would very quickly

take a potential customer to the product line for help; Max, on

the other hand, would solve problems himself. He would design

the interface and work out the program on his own, as "sales

engineers" at remote sites throughout the world typically had to

do.

Remote sales of large computers, like the

PDP-6 and later the PDP-10, were unique opportunities for

expansion. Such a sale, with al the support and spares required,

sold for more than a million dollars and provided a base to open

a service office and build small computer sales. But experienced

people were scarce, and those who were used to working far from

Maynard were in particular demand; so some of them moved around

frequently as new opportunities opened up throughout the U.S.,

Europe and Canada, as well as Australia, Latin America and the

Far East. Once an operation was established, people with

different skills and personalities were needed to manage; and

the pioneers moved on to new frontier territory.

For example, the first three people hired to

maintain the PDP-6 in Perth -- Peter Watt for software and Robin

Frith and Bob Reid for the hardware -- ended up in pioneering

roles elsewhere in the world, as did Ron.

Bob Reid had worked for Ron at the University

of new South Wales. "Then when I left the university to work for

UNIVAC, Bob went to Germany and worked for Telefunken, designing

computers," says Ron. "When we needed people for the PDP-6, I

had someone track down Bob, hire him and take him to Maynard for

training. Bob

worked on the PDP-6 in Australia for a time, then went back to

Germany and worked in Bonn and Aachen on the PDP-6s that had

been sold there." Bot later worked on a variety of projects for

DEC in the U.S. and was the designer of the DECSYSTEM-2020 CPU.

Peter Watt was hired in June 1964 as an

application engineer and went to Maynard to learn about the

PDP-6 software. He worked on the Perth software for a year

before going to support the first PDP-6 in the United Kingdom at

Oxford.

Robin Frith had attended a modules seminar

given by Harlan Anderson back in December 1963, when J. J. Masur

was operating as DEC's representative in Australia. Harlan

offered him a job and sent him back to Maynard to learn about

modules. While he was in the U.S., Robin helped build and check

out PDP-6 number 4 before installing it in Perth in December

1964. Later, he returned from Perth to Sydney as General Manager

for Digital Equipment Australia, taking over from Ron Smart who

became New York district manager under regional manager Dave

Denniston. About a year after that, Ron moved to Maynard and

became the first manager of what eventually became the General

International Area.

When Ron went to Maynard in 1967 to work for

Ted Johnson, then vice president of Sales and Service, DEC's

operations in the U.S., Europe and Canada were organized as

regions. Part of Ron's responsibility, along with running the

Export Dept., Order Processing and Sales Administration, was to

manage and start operations elsewhere in the world.

Australia was set up as a subsidiary, a local

company owned by DEC to provide dire3ct sales and service to

customers. In Japan, DEC was represented by Rikei Trading

Company, which sold mainly into laboratory and scientific

applications. In 1968 a DEC branch office was opened in Tokyo.

In addition, because of its growing

international reputation and because many people from other

countries received their technical training on DEC computers at

U.S universities, orders sometimes came directly to Maynard from

countries where DEC had no representation at all.

By 1972 Australia/Japan/Remote was a $7

million a year operation -- almost as large as all of DEC was

when it started in Australia in 1964. Renamed "General

International Region," it quickly grew to $16.8 million by 1973,

and reached $1.1 million in 1977.

Int he early 70s, worldwide remote sales were

handled by a small group of travelling salesmen -- Tom Robinson,

Stewart Wright and Mario Martinello. (Mario is now Sales Group

manager for Central and South America).

Bob Buckley, who joined Ron as administrative

assistant in 1972 (he's now executive director of DECUS GIA),

recalls that the headquarters Sales staff consisted of just

himself, Ron, two secretaries and a person who handled order

processing. "Ron

would go off for three or four weeks at a time, and we'd handle

all the mail. Everyone participated, it was pretty much a

ma-and-pa operation."

"When vying for selling and advertising money

from the product lines, Europe and the U.S. would do a full

presentation, complete with a staff, flip charts and overheads,"

remembers Bob. "We, who were nowhere near that sophisticated,

had to rely on verbal persuasion. Looking back it was a very

exciting period; at times it seems impossible that GIA has grown

so rapidly in so many ways in such a short time."

Theoretically, GIA could have been managed

from almost anywhere in the world, but having headquarters near

Maynard provided easy access to Manufacturing, to the product

lines, and to support functions that, as a small operation, they

couldn't afford to develop for themselves.

"Musch of what we were doing was new for the

company and required a lot of follow-up and communications,"

explains Bob. "We were shipping to countries we had never

shipped to before, and coping with the shifting legal

requirements of a wide variety of countries."

"We didn't give discounts at all," notes Ron.

"We needed all the money we could get to be able support the

equipment if it got into trouble. Typically you'd add as much as

a third to the hardware price to cover such things as spare

parts and installations."

Some remote countries, like the Philippines,

sent orders that, while tempting, had to be turned down because

there was no way DEC could properly support the equipment.

To decide where DEC should do business, Ron

first looked at the gross national product (GNP), a relatively

good index of the total amount of business in a country and

hence of the need for computers. "The revenue from all computer

sales in a country tends to be a somewhat predictable percentage

of the GNP," explains Ron. "More specifically, if certain

applications are done in country X and also in country Y, then

the ratio of potential computer sales (for that application) to

GNP would tend to be the same in both countries. So by looking

at the GNP, you can get a rough estimate how much revenue you

might get if you set up a business there.

"In the early 70s, the total computer market

in most countries was approaching 1% of the GNP, and DEC could

expe3ct about 5 or 6% of that 1%.

So you could quickly calculate whether it could be

worthwhile for DEC to consider getting involved in a new

country."

Another important consideration was IBM. "If

IBM wasn't there, then probably nobody had ever heard of a

computer," says Ron. Concentrating on sales of mainframe

computers for batch data processing applications, IBM let people

know what computers were about and left minicomputer-type

applications open for DEC.

"To get started in a country," says Ron, "we

would go to universities and government research institutions

and begin to attract interest, the way I was attracted to DEC,

as a company with real-time minicomputer and opportunities to

meddle with the hardware as well as the software.

"In those days too," Ron continues, "we had

the worldwide community of nuclear physicists spreading the word

about our products. Every nuclear physicist knew DEC was the

place to go for real-time instrumentation and for the processing

of experimental data. Many of our large PDP-6s and PDP-10s were

used for nuclear physics. Later our reputation spread throughout

other communities of scientists and engineers."

Information about computer opportunities in

one country, such as the U.S., had to be translated into the

context of other countries, to decide where to concentrate GIA's

limited resources. "With

time we became more sophisticated about this," says Ron. "We

would take the GNP, segment it by industry, look closely at the

industries we knew we could sell computers to, then translate

this information into computer applications and product line

opportunities."

There was one threshold point for setting up

business through a rep, and another for selling directly. When

looking for a good technical representative in a new country,

DEC would typically try to get the same one that U.S. and

European electronic instrumentation companies used. Often these

were OEMs (Original Equipment Manufacturers) of ours," explains

Ron, "so a a rep who knew about our machines from working with

us, would be in a good position to sell and service products

from the OEM that had our computer inside it. This was a very

synergistic relationship."

The approach to a country varied to meet

local national need. For

instance, India, with a very large GNP, has a a relatively small

computer market because of a variety of government controls and

restrictions aimed at developing local industry. DEC worked

through Hinditron, the same distributor Tektronix and Fluke

used. "They are very good," Ron emphasizes. "They enabled us to

talk with the government and to find rational ways to satisfy

their local industrial development objectives and still import

the products they needed from us. In other countries with large

business potential we had much more difficulty arriving at a

rational understanding.

"Our first OEM in India was the Indian

government itself. They set up an organization to put together a

defense system using our computers. Later that same organization

worked on computer applications for offshore oil rigs, once

again with DEC computers."

By 1977, GIA was doing business in 17

different countries. "We set up an accounting system with profit

and loss (P&L) calculated at the country level," explains

Ron. "This facilitated the decentralization of business

decision-making and helped the countries lean how to operate

within corporate business objectives."

"Throughout its history, GIA was the fastest

growing and most profitable area of the whole company -- it had

to be profitable to compete with the U.S. and Europe for

funding from the product lines. We had to convince the product

lines that it was a good idea to invest in places with cultures

they didn't understand.

:Our profitability was helped by the fact

that we were able to measure at the country level and make

corrections, adjusting the country prices and terms to achieve

our profitable growth goals in each country."

In 1971 when Ron Smart needed someone to

start up business in Mexico, he called on Dave Dodge whom he had

worked with in the New York district. "Dave was super good

technically and a good salesman and contract negotiator,"

remembers Ron. "Also, he was the kind of person who could manage

on his own."

After that first contact with Dave, Ron

called on him repeatedly, having him start up DEC's distributor

and/or subsidiary operations in Argentina, Chile, Brazil,

Bolivia and Iran.

"Ron just said -- go off and do it. I

frequently went into those countries alone. I spoke enough

Spanish and Portuguese to get by. Our legal and financial

contacts were often associates of firms that we dealt with in

the States. Also, most of our customers had been educated in the

States or in Europe. They knew our equipment from using it in

their studies or research; so when they went back to their

homeland they bought DEC computers even though they had to do so

under 'remote terms and conditions' They usually spoke very good

English.

"The most difficult task when going into a

new country was to figure out the local cultural nuances.

There's an old Brazilian saying that 'the shortest distance

tween two points is a spiral.' You to come at problems from the

side, even pretend that you're not approaching the problem, even

seem disinterested.

"The best thing about working in remote

locations was that you had to be prepared to do almost anything

yourself. In South America, the distances were so vast that on

any given trip you might have to design a standalone controller

implemented in DEC's flip-chip logic modules, hep a customer

debug a computer interface, give a presentation on the internals

of the PDP-10 interactive operating system, and discuss with a

local attorney the tax implications of a DEC contract of sale

executed in that country.

"As DEC's market share increased and the

decision to set up a new subsidiary was agreed upon, the

emphasis of the work changed from technical to business matter.

International banking, patents and trademarks, import duties,

and pricing and support policies became a part of your everyday

work, until, finally, a new subsidiary was born."

Dave, who now does systems engineering for

the Government Systems Group, has been with DEC almost 18 years.

Before working for Ron, he was district sales manger for the

Great Lakes, and before that branch manager for Parsippany,

N.J., and before that a "logic modules applications engineer,"

working out of Parsippany.

DEC is the second largest computer company in

Canada in terms of revenues and number of computers installed,"

notes Dave Whiteside, president, Digital Equipment of Canada

Ltd. In the annual ranking of Canadian companies published by

the Financial Post, based on FY81 revenues ($252 million

Canadian), DEC was number 228. (That's Canadian companies and

Canadian revenues).

Canada has only 24 million people, and a

gross national product that is about 10 percent of that of the

U.S. But the Canadian and U.S. markets are very similar. "What

sells in the U.S., generally sells here," says Dave.

There are no Canadian-based computer

manufacturers, but Canada does have companies that are strong in

specific computer-based applications, such as word processing

and communications. Because of the need to cope with the vast

distances between its pockets and population, Canada tends to be

leader in communications technology for both voice an data. The

area around Ottawa is referred to as the "Silicon Valley of the

North," with research and development headquarters for two of

the world's largest suppliers of communications equipment --

Northern Telecom and Mitel -- and other related high technology

businesses.

"The proximity of such companies to our

headquarters in Canada gives us a great opportunity to develop

strategies that could be included int he corporation and improve

our understanding in our related product areas -- such as

office," notes Dave.

Canada consists of four districts. The

Western District, including Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta and

British Columbia, extends for 2000 miles. It accounts for 29

percent of the Canadian business.

Ontario (exclusive of Ottawa area), with headquarter sin

Toronto accounts for 39 percent of the business. Ottawa government and

the Maritime Provinces contributes another 19 percent. And

Quebec provides the remaining 13 percent.

The French language is unique to Quebec. "We

trade product literature with DEC in France and make

modifications to reflect Canadian usage," explains Dave. "For

instance, in France the accepted word for 'computer' is

'computer,' but in French Canada it is 'orindateur.' There are

also a few minor grammatical differences between the two

varieties of French -- such as accents on capital letters. This

means word processing systems made for France are not entirely

applicable here. Fortunately, DEC's new personal computers have

a small processor in the keyboard itself which can be programmed

to deal with variations in symbols; so it should be relatively

easy to develop a keyboard specifically for Quebec, opening new

markets for us there.

"I think the biggest challenge for us is to

try to take a country that is fragmented by distance and build a

company that is unified," say Dave. "It's further from Toronto

Vancouver than it is from Toronto to Mexico City. It takes just

as long to fly from Ottawa to Vancouver as it does to fly to

Munich. Ireland is closer to Halifax than Vancouver is. It's a

huge country -- 50000 miles wide, covering 5 time zones."

Every major university and educational

institute in Canada uses DEC computers. VAX has become the

standard in computer sciences courses. "Researchers at these

institutions use DEC computers for advanced work that leads to

new applications of our equipment that spread, in a ripple

effect, right across the world," says Dave.

Manufacturing, Distribution and Control

(MDC), which handles such industries as mining, oil and food

production, is the largest product line, accounting for about

$22 million (Canadian) out of about $170 million in sales. One

of its biggest sales was to the Saskatchewan Wheat Pool,

automating inventory control and administrative functions at 500

grain elevators throughout the province.

DEC started manufacturing and put deep roots

in Canada very early. Canadian

customers began to appear back in 1961. For instance, the Atomic

Energy of Canada Ltd. at Chalk River, Ontario, designed a system

that ran on the PDP-1 for recording and processing the

voluminous data accumulated by instruments used in studying the

energy of nuclear particles.

As other markets in research centers and

universities continued to open up, DEC hired its first employee

in Canada, Denny Doyle, in March 1963. On May 1, 1963, an 1100

square foot office at 1301 Richmond Road opened its doors and

Digital Equipment of Canada Ltd. -- with a staff of two -- was

officially born.

Manufacturing started in October, 1963. An

abandoned woolen mill in Carleton Place, Ontario, was purchased;

and by the end of 1964, there were about ten people involved in

the manufacture and sale of logic modules. Shortly after the

introduction of the PDP-8, the first mass produced minicomputer,

Canada got involved in all aspects of its manufacture from the

module assembly to backplane wiring to system checkout. In 1966,

they began experimenting with semi-automatic wire-wrapping

techniques; and, as a result, the Carleton Place facility soon

became the backplane wire-wrapping facility for DEC's worldwide

needs.

In 1971 when sales in Canada amounted to 412

million Canadian, DEC purchased 55 acres of land in Kanata (a

city just west of Ottawa), built a facility and moved

manufacturing, Computer Special Systems and Canadian

headquarters there.

Originally, Canada was managed like a U.S.

region as part of North American Sales. In 1979, it was made

part of GIA to better focus on international issues.

Today, Digital Equipment of Canada employees

over 1800 people -- about half of them (including 500 in

Manufacturing) at the headquarters facility in Kanata, Ontario,

(a suburb of Ottawa) and the rest in 33 sales and service

offices from coast to coast. In 1982 revenue, including

manufacturing, amounted to $295 million (Canadian).

Digital also supports over 50 OEMs, who add

value to the company's products and resell aa total package to

the end user. These firms employ over 1000 people and generate a

quarter billion dollars of revenue.

"Among the countries int eh Country

development Region (DCR) that we actively pursue, Brazil has the

largest computer market, Mexico the second largest," says Fred

Gould, Sales manager of the Country Development Region. "In

terms of profitability, DEC did very well in Brazil last year.

But we would like to be doing anywhere from 4 to 10 times more

business there. Unfortunately, we are limited because the

Brazilian government reserves the minicomputer market for

Brazilian-owned minicomputer companies."

DEC's business is also restricted in Mexico.

Not only are there short term currency issues, but there are

also market restrictions. The microcomputer market is reserved

for Mexican-owned companies and to participate in the

minicomputer market, multinational computer firms, like DEC,

must submit plans for manufacturing in Mexico. Once a company

has an approved plan, it gets a bigger import quota than it

would if it wee considered as simply a distributor.

Currently, CDR's greatest growth is in the

Far East. DEC has sales offices in Hong Kong and Singapore and

distributors in South Korea and Taiwan. DEC also has customers

in Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, the Philippines and mainland

China who buy from the Singapore and Hong Kong offices and

through OEMs.

"Singapore, which is a 250 square mile

country with a population of 3.5 million, is one of the easiest

countries to do business with," Fred points out. "They want

computer technology -- the ability to use the computers and also

the ability to add value to computer systems. But their approach

is the opposite of that of Brazil and Mexico. They encourage

multinationals to come in. They set up a school to train local

people to do the jobs companies need filled. they provide

incentives and make it very easy for foreign corporation to get

established. Also, unlike other places where the movement of

profits out of a country are limited and taxed, in Singapore a

company ahs total freedom of movement of investment and profit

money. So Singapore is a very favorable place to do business."

In addition to its other challenges, CDR

faces delays of up to 18 months in obtaining export licenses from the U.S.

government for some of the geographies. Despite these issues,

there are now about a hundred DEC computers installed in

mainland China. Most of them were placed there by OEMs, but

about a dozen were supplied directly by DEC, through the Hong

Kong office, mostly for educational applications. DEC computers

also perform administrative functions at the Customs Houses in

Canton and Shanghai.

The CDR countries have a total gross domestic

product greater than that of the U.S. and, over time,

notwithstanding the current economy, the average growth rate in

these countries collectively ahs been considerably greater than

that of the U.S. or Canada or Europe. "Its long term importance

to the company is far greater than the present size of its

business," says Fred. "Last, year, which was not an easy one for

CDR, we did not achieve our budget -- but we still grew by 50

percent."

Australia

With only 15 million people in a territory

the size of the continental U.S., Australia has widely separated

pockets of population. In the early days, whenever a large

computer like a PDP-6 or PDP-10 was sold in a new area, DEC had

to open a new service office and hire one or two people just to

support that one machine. And the people hired had to be highly

technical, able to independently solve whatever problems might

arise.

At the end of 1965 Digital Equipment

Australia consisted of just two people in Sydney and three

others 3000 miles away maintaining the PDP-6 in Perth, (See

related article "going International"). But sales of the then

recently introduced PDP-8 minicomputer soon flourished in

Sydney. In August 1966, Albert Cushcieri was hired as the first

minicomputer field service engineers. (The next year he joined

the sales force. He is now the company's only four-time winner

of the DECathlon, DEC's highest award for outstanding sales

performance.)

By 1970 the staff consisted of 37 people.

Since then sales have soared to $68 million (Australian), while

the number of employees has grown to about 800 in 19 offices

throughout Australia.

One of the more interesting applications is

in Tasmania, a large island off the southern coast (toward

Antarctica), with a population of about 250,000. That state's

education department has for several years had a full computing

curriculum in the elementary schools. Typically, each school has

a classroom with three terminals hooked up to a PDP-11/34 shared

with several other schools. (Tasmania is reputed to be the

birthplace of many of Australia's computer experts).

New

Zealand

Early ales in New Zealand were made out of

Sydney, Australia by Robin Frith and Alan Williamson. The first

machine sold into the country was a PDP-8 on July11, 1966. Early in 1970 Mike

Andrews was hired as the fist employee in New Zealand. He opened a Field

Service office in Wellington. He is now New Zealand Field

Service support unit manager.

In 1971, the first New Zealand salesman was

hired and for several years after that DEC was virtually the

only minicomputer company successfully selling in New Zealand.

By 1975 there were 250 computers installed.

In the late 70s, New Zealand grew

dramatically, installing a massive network for the Dept. of

Health under the leadership of Jim Meem.

Annual sales and service revenue there has

grown to about $11 million (New Zealand dollars0, and there are

now about 100 DEC employees at six offices in New Zealand.

Digital

Japan today

DEC opened tis first Japanese branch in Tokyo

in 1968 with a half dozen employees. since then Digital Japan

has grown at an average rate of 40% per year to reach annual

revenues of well over $100 million. Because of this rapid

growth, about 400 of the present 850 employees have been with

the firm for just two years or less.

The main officers, headed by Edmund Reilly,

are located in the 60-story Sunshine 60 Building in Tokyo's busy

Ikebukuro area. Outside Tokyo, the company ahs six sales

offices, 18 service centers scattered rom Hokkaido to Kyushu and

a quality assurance center in Chiba. The Japan operation incudes

Sales, Computer Special Systems, Field Service, Software

Services, Educational Services, Finance and Administration,

Personnel and the newly formed Japan Research and Development

Center -- part of DEC's Central Engineering organization.

DEC's customers in Japan include

universities, hospitals, government agencies, banks, airlines,

research institutions, railway lines and corporations. A total

of 3000 DEC units are in operations. A large portion of these

are used by universities and electric equipment manufacturers

throughout Japan.

Japanese

give DEC high marks

DEC's products ranked first in customer

satisfaction in a recent survey of Japanese minicomputer users

conducted by Nihon Keizai, a leading publisher of business

newspapers and trade journals. Customers gave DEC high marks for

overall satisfaction with product use. Mitsubishi Electric came

second while IBM and Panfacom tied for third. They were followed

by Hitachi, Yokogawa Hewlett-Packard, Oki Electric, Toshiba,

Data General and NEC.

The survey of 1,092 major minicomputer users

throughout Japan was taken earlier this year. The results, based

on a 49 percent return, were announced in a recent issue of

Nikkei Computer, a magazine affiliated with Data Communications

in the U.S. Questions were asked in five categories. DEC ranked

first in operability and processing capacity and second in

reliability and expandability.

"DEC, which received the highest rating in

overall satisfaction, stands either first or second in most

categories, noted Nikkei Computer. "DEC has achieved the same

status in minicomputers that IBM has achieved in mainframes. The

16-bit capacity that is the mainstay of minicomputers was

brought about by the best-selling PDP-11 series which DEC

announced in 1970. DEC's high customer satisfaction is credited

to the total perfection of their systems, reflecting their long

history."

DEC's VAX computers received overwhelmingly

high marks from users, ranking first in all areas of comparison

with 19 competitive models.