by Richard Seltzer, from DECWORLD, the company

newspaper, July 1983

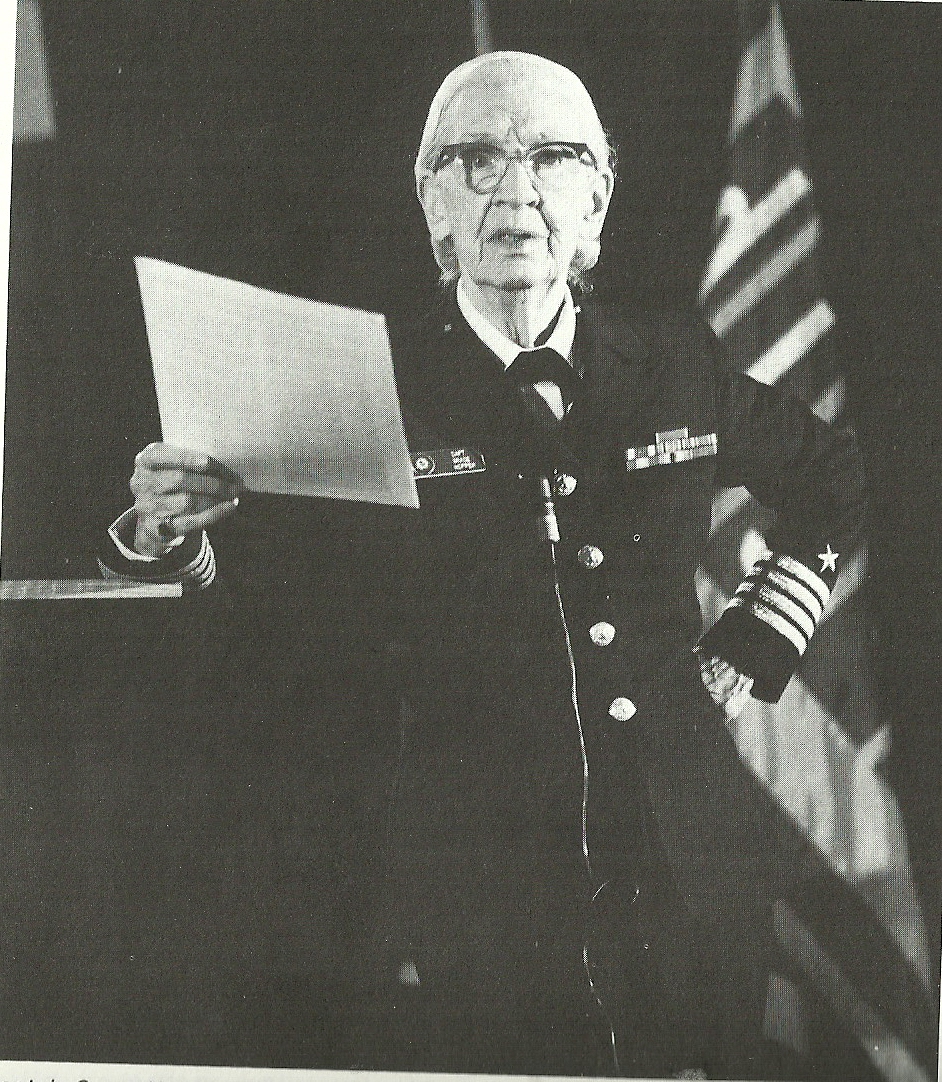

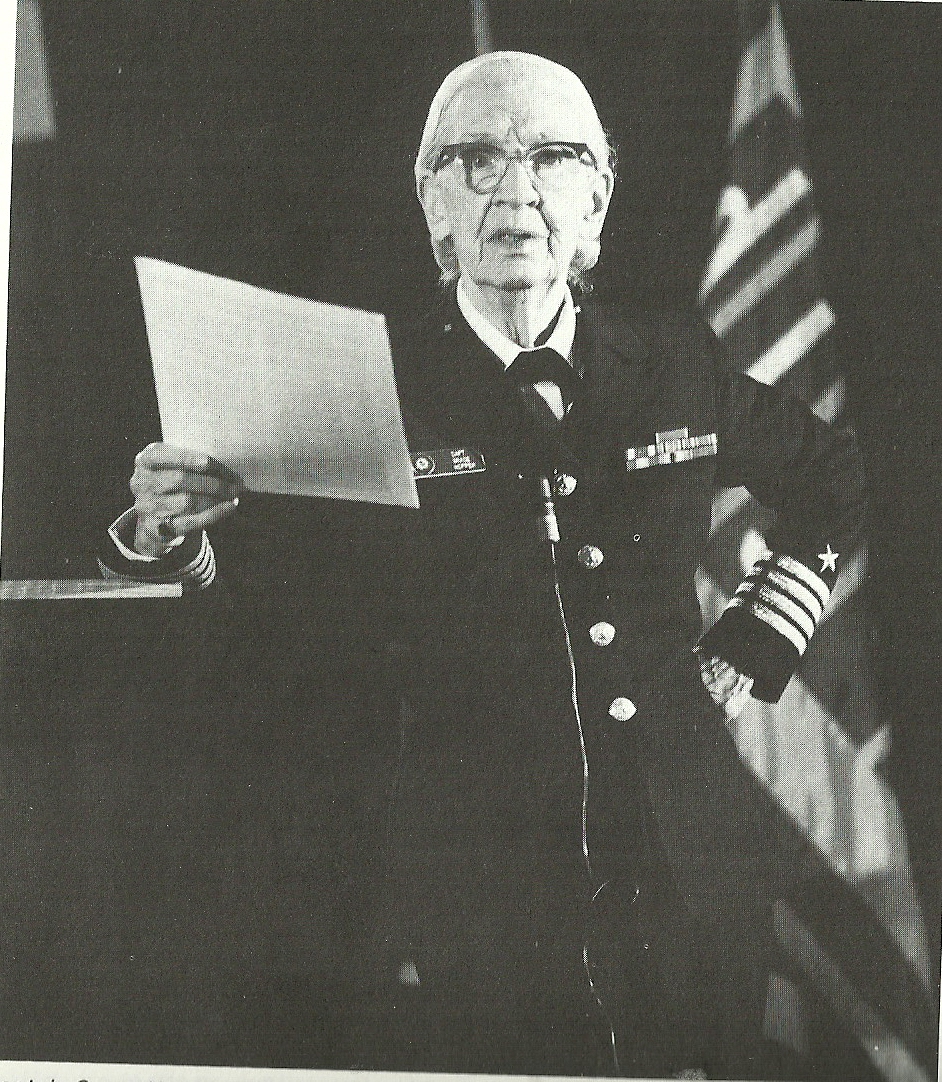

Proud and feisty, Captain Grace Hopper talked

about computers as she has known them since 1944 and as common

sense tells her they should be in the future. She told of how she

leads her small Navy crew of programmers, educates her bosses in

the Pentagon, and haunts anyone who says, "But we've always done

it that way." The Digital audience, convened at the invitation of

the Communications Industry Group in Merrimack, NH, to hear

"thought on innovation," responded to her non-stop hour and a half

barrage of wit and wisdom with a standing ovation. The following

article is based on her remarks.

"Typically, people make plans for the use of

computers based on what they are doing now and the equipment they

have now. They fail to review those plans int he light of what

they will be doing and

the equipment that will

be available in the future. This

is a critical review that has to be made of every plan, no matter

what you're doing.

"Probably the most dangerous phrase that can be

used in any computer installation is, 'But we've always done it

that way.' That phrase is forbidden in my office. To emphasize

that fact, I keep a clock that operates counter-clockwise. The

first day, you have a little trouble telling time. By the second

day, most people have discovered that what used to be 10 of is now

10 after. By the third day, they recognize there was never any

reason why clocks had to run clockwise.

I'd like to give each one of you a small gift.

If during the next 12 months anyone of you says 'But we've always

done it that way,' I will instantly materialize beside you and

haunt you for 24 hours. I know it works because I've already had

over a hundred letters thanking me for haunting people. We can no

longer afford to use that phrase.

"We've got to take chances, try new things and

move towards the future. We've also got to recognize that's not

going to be easy. But if you let yourself get frustrated, you're

licked from day one.

"Once, an officer who had to take his squadron

out to an aircraft carrier was told he'd have to leave all his

maintenance records in the Naval Air Rework Facility. Well, this

didn't please him. He wanted the maintenance records for his

planes with him. So he bought a personal computer, made friends

with a programmer who could copy his maintenance records onto it,

put the computer into a case that could fit behind his seat, and

flew off to the carrier with all of his maintenance records in the

computer. When he

came back, he told the Department of Defense Computer Institute

about it. Somebody there said, "Are you supposed to do that?" He

said, "I didn't ask."

"Remember, on many occasions, it's much easier

to apologize than it is to get permission. A ship in port is safe,

but that's not what ships are built for. We've got to sail the

sea, because that's what ships are built for."

Grace recalled her first encounter with a

computer, MARKI, the world's first large scale digital computer,

on July2, 1944. "It was 51 feet long, 8 feet high, 8 feet deep, in

a magnificent glass case. It had 72 words of storage and could do

3 additions a second. It would get two quantities from memory, add

them together and put the answer back three times a second or once

every 333 milliseconds (thousandths of a second). That sounds

pitiful today, but it was the first tool that assisted the power

of man's brain instead of the strength of his arm.

"Not until 1951 was there a commercial

electronic computer -- UNIVAC I. It had a thousand 12-character

words of storage. In other words, UNIVACI was a 12k microcomputer,

but it ran all the premium notices for Metropolitan Life. (We seem

to have forgotten what a dedicated computer can do.) It did an

addition in 282 microseconds -- a thousand times faster.

"By 1964, the first of the CDC 6400s came out.

It could do an addition in 300 nanoseconds, 300 billionths of a

second -- another thousand times faster.

"Now, we need a system that adds in 300

picoseconds, trillionths of a second -- another thousand times

faster. We need it right now, but we can't build it the way we've

been building the dinosaurs of the past. We're going to have to do

something different.

"We need it because we're soon going to have to

face some major problems. The population of the world is

increasing, so we have to increase food and water supplies. The

biggest assist to increasing food supplies would be better

long-term weather forecasts. We don't yet have a computer which

can run the full scale model of that big heat engine made up of

earth, atmosphere and ocean. We're not even sure of our techniques

because we've never had the computer power to run it. Up until a

few years ago, we didn't have the data to feed into those models.

But now we have satellite photographs that when fully enhanced by

computer enable us to tell how high the waves are in the middle of

the Pacific and what the temperature of the ocean is 20 feet below

the surface. But to fully enhance a satellite photograph takes ten

to the fifteenth power (one quadrillion) arithmetic operations.

That takes close to 3 days on our best computers today.

"We're going to have trouble getting the

powerful new computers we need because we're reaching the

physi8cal limit of the speed of light or electricity. Think of a

length of wire. In a microsecond (millionth of a second)

electricity can go 984 feet.

In a nanosecond, a billionth of a second, it goes 11.8

inches. In a picosecond (trillionth of a second), the distance it

goes is no bigger than the little pieces you get from chopping

something up in a pepper grinder.

"I said I wanted to add in 300 picoseconds, a

third of a nanosecond. But electricity doesn't go fast enough to

cover the distance in a computer from memory to adder with the

numbers to be added and then back to memory with the answer in

that short a time. So what can I do? I can't wait for our bright

young engineers to find some way to get beyond the velocity of

light. I need that computer in the next five years.

"Back in the early days of this country, when

heavy objects had to be moved around, people used oxen. When they

had a big log that one ox couldn't budge, they didn't try to grow

a bigger ox. They used 2 oxen. Likewise, when you need greater

computer power, you don't have to build a larger computer; you can

get another computer.

:Long ago we should have recognized that the

answer is not to build bigger and bigger mainframes, but to build

systems of computers. That is where the future lies.

:One such system is being put together at NASA. It consists of 128 by

128 processors (chips). That 16,384 processors all in one system.

We think it's going to be as big as MARK I. There's one cabinet

that holds the processors, a second cabinet holds the input/output

and control and a third cabinet that's a PDP-11/34, because

obviously, you can't run 16,000 computers without having a

computer to do it with.

:Each of those processors will receive one

pixel (small piece of graphic information) from the satellite

photographs, including position, color, brightness. It will be used to hunt

for oil and minerals. That's the largest integrated system of

computers that I know of so far.

"You're going to see more and more systems of

computers in business applications as well. Inventory and payroll

don't belong on the same computer. We put them together because we

could only afford one computer, but that is no longer true. It

doesn't matter whether the computers are all in one room or spread

all over the world. We

now have the communications and the software to have those

computers work together.

"I'm deeply grateful to every manufacturer of

micro and minicomputers because my guess is that's the real

future. The micros, the minis, the communications.

"We're only at the beginning of this industry,

at the Model-T stage. We're at the stage of that first airplane

that I flew in 1924, built out of linen and wood and wire, a

biplane with an open cockpit. It went up about 150 feet and

floated along about 80 miles an hour. We haven't got the jets yet,

we're only at the beginning.

The future is up ahead of us."

Grace Hopper, a Captain in the U.S. Naval

Reserve, likes to be introduced as the third programmer on the

first large scale digital computer so she "can remind you that the

first large scale digital computer was a Navy computer, operated

by Navy crew in World War II."

In the early 1950s she was instrumental in

developing the first compiler -- the software that made it

possible to communicate with a computer in words rather than

numbers and to have a computer do more than just arithmetic. Her efforts led to the

development and widespread use of COBOL and other high level

computer languages.

At the age of 60, on December 1966, the

'saddest day' of her life, she was officially place on the Naval

Reserve Retired List. Then

just a few months later, she was called back for six months of

temporary active duty, her assignment: to standardize the high

level languages and get the whole Navy to use them. As she put it,

"So far, it's the longest 6 months I ever spent in my life." Today

[1983] she's still working on that task and, in other ways,

letting the armed forces and the U.S. government know how they can

use common sense to eliminate waste in their vast data processing

operations.

She concluded her talk to the Communications

Industry Group by saying "I've had such a happy time the last 15

years. It's been busy, challenging. I have loved every minute of

it. I have also received most of the honors that are given to

anyone in the computer industry. Each time I have received one,

I've thanked them, then told them, as I tell you: I have already

received the highest award I will ever receive, no matter how long

I live, no matter how many more jobs I have. And that has been the

privilege and responsibility of serving very proudly in the United

States Navy."

Captain Grace Hopper, U.S. Naval Reserve,

computer pioneer. After she retired from the Navy in 1966, the

Navy called her back and she worked for them for another 20 years,

finally retiring in 1986, at the age of 80. Then she went to work

for DEC as a consultant, until her death in 1992.

seltzer@seltzerbooks.com

privacy

statement