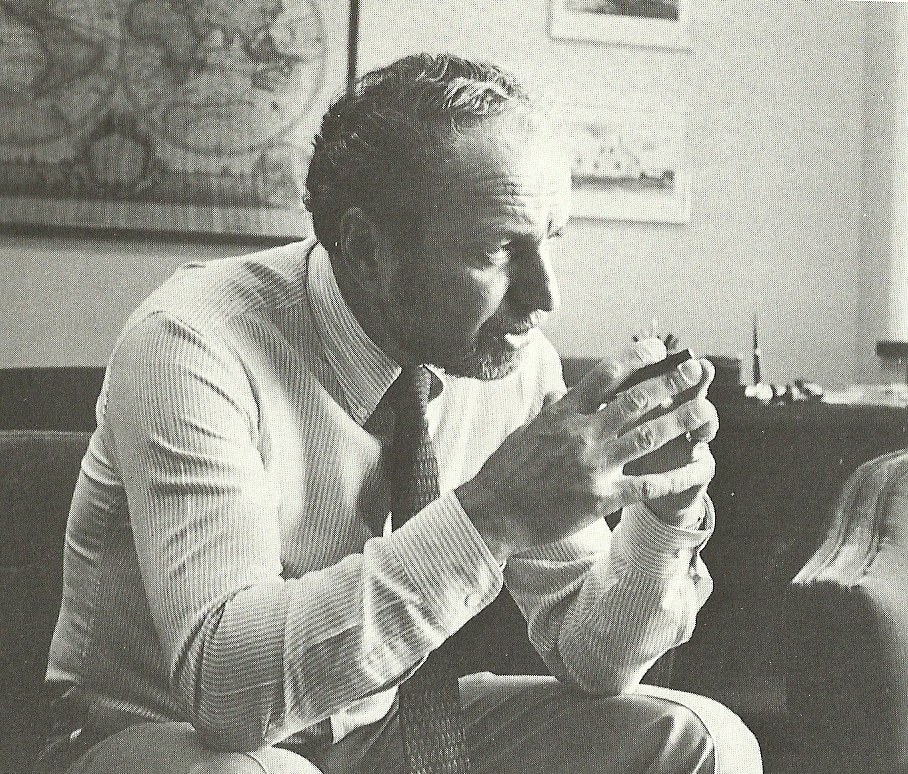

Ken

Olsen, President of DEC

by Richard Seltzer, from DECWORLD, the company

newspaper, September 1982

From modest beginnings in an old mill in

Maynard, Massachusetts, DEC

(Digital Equipment Corporation) has grown, in just 25 years, to be

the second largest manufacturer of computers in the world

(according to published surveys of the worldwide industry). Its

products -- from tiny microprocessors to large mainframe computers

-- have become models

of excellence in diverse markets and applications, helping

individuals as well as schools, governments, research institutions

and large and small companies of all kinds to perform their work

more efficiently and effectively.

To respond rapidly to market needs, DEC divides

its business into manageable pieces and delegates responsibilities

to many individuals, rather than concentrate them in the hands of

a few individual initiative, integrity arid accountability are

encouraged at all levels. This work environment means that the

talents, inspirations and efforts of many different people can

quickly be brought into play to meet the shifting challenges of

the highly competitive computer business.

In many ways, the most recent year was one of

the most challenging and satisfying in the company's history,

demonstrating the vigor and flexibility of this large organization

and the resourcefulness of its 67,000 employees.

"Our twenty-fifth year was a great one." says

Ken Olsen, President. "We grew 20%, invested heavily in new

products, were able to offset strategic price decreases by

reducing our costs in than ten years. That's not bad in the middle

of a worldwide recession. We have reason to be proud.

"We have suffered from having good times for

too long." he explains. "People, countries, economies and

companies cannot tolerate good times for very long. It's not

healthy.

"We had several years when things seemed too

easy. Our sales people had to spend most of their time telling

customers how long they'd have to wait to get our products. Demand

for our existing products made it impossible for us to develop new

products. Throughout the company, we developed bad habits.

"Two years ago I was frustrated. It took three

years to develop a new product. It took four months to get a

printed circuit board. We had committees on top of committees to

check everything.

"But now," says Ken, "after a lot of effort and

the recession, we are good. Now you can get a printed circuit

board in a week; and the new products move so fast, it's hard to

keep up with them.

"We did quite well with our old ways of doing

things," notes Ken. "Now the way we've started turning things

around, we'll be so efficient I don't worry about anybody in the

world."

Win

Hindle joined DEC in 1962 as assistant to the president. He was

promoted to product line manager in 1964 and to vice president

and group manager in 1967. He became vice president, Corporate

Operations in 1976. (Photo by Peg Blanchet, U.S. Area News)

"When I started at DEC in September of 1962,

the company had about about 400 active employees. It was growing

well/ That year we did sales of $8 or 9 million. Of course, at

that time we were a privately held company, and were not

disclosing our sales and earnings information to the outside

world.

"My first Job was assistant to Ken Olsen. He

gave me a variety of assignments. For instance, I started a formal

engineering scheduling system to ensure that engineering got done

on time, and I also recruited some engineers and sales people.

"We had a small Personnel Department, but we

had very definite ideas about how to handle people and how people

should manage. We had a strong feeling for the individual and

wanted to be sure our Personnel policies enabled us to provide

Jobs that people would be excited about and could accomplish, that

had goals and measurements, Many of the same things we talk about

today, we were Just as interested in then,

"We recruited mostly in the Massachusetts area.

I think at the time I Joined we had only one sales office and that

was in Los Angeles, where Ted Johnson was the manager. Then we

opened a second one in New Jersey, just outside of New York. A

year or so later, when we needed to open a sales office in

Chicago, I was sent there to hire someone to open and manage it.

We had a Works Committee that was the chief

policy-making body, as the Operations Committee is today. Ken was

the chairman and, as his assistant, I was the secretary and had to

prepare the agenda and write the minutes. In that committee we

decided that we were spending too much time on current issues and

not enough on long range planning. So we decided to get away from

our usual settings in the Mill and hold a meeting somewhere else.

Later we decided we should really get off and away, not Just go to

a motel. So we had a meeting at somebody's cottage in the woods.

That's where the name "Woods Meeting" came from -- a meeting away

from the plant where you consider longer range issues.

"In those meetings, we would plan the size of

the company over the next five years. As it turned out, when we

compared our actual performance to the long range plans, we found

that we had usually grown faster than anticipated five years

before."

PDP-6 and the product

line structure

"We did, however, face a very critical problem

around the time of the introduction of the PDP-6 in 1964. That

machine was larger and more complex than we should have attempted

considering how small the company was at the time . We had

difficulty finishing the hardware engineering and the software,

and all the best engineers in the company were recruited for that

project to try to make it work. While they were concentrating on

the PDP-6, where we were losing money, no one was working on our

other machines -- the PDP-5, PDP-7 and our modules -- that were

making money.

"It was at that point that Ken realized that we

had to change the organizational structure so that we wouldn't

arbitrarily put all of our resources into one product and to make

sure that we spread our resources in the same proportion as we

were seeing success.

’So it was out of that experience with the

PDP-6 that the product line structure in the company came about.

Each product line budgeted resources that nobody else could take

from them, and those resources had to be planned by the beginning

of each fiscal year, and the plans had to show how we were going

to make a profit.

"We could have gone out of business because of

the PDP-6 if we hadn't made those changes. Fortunately, we were in

good shape with our other products and they more than made up for

our losses on the P'DP-6, thanks to that change in our

organization that protected their resources.

"Most of the first product lines were oriented

around hardware products rather than markets or applications, and

they each had their own engineering departments. In other words,

instead of a central engineering department, we had PDP-4

engineering, PDP-5 engineering, PDP-6 engineering and Modules

engineering, along with a few smaller projects.

"We still had Sales, Manufacturing and Field

Service as separate functions. The product lines managed the

marketing, the engineering and the planning. Each of the product

lines asked for a certain amount of resources from Sales,

Manufacturing and Service and negotiated their needs with the

functional managers.

"Each product line started with Just the

resources it had at the time the new structure went into effect.

Because the PDP-6 had already taken away many of the engineers,

these groups had to rebuild, either by hiring these engineers back

from the PDP-6 or by recruiting new ones.

"You could propose adding resources, but we

didn't add very many during the first year. It took us a while to

get into the new organization.

"In 1965, Ken asked me to become the manager of

the PDP-6. I was already product line manager for three small

product lines and was asked to add the PDP-6 to what I already

had.

"After looking at the situation and seeing how

bleak it was, I recommended to the Works Committee and they agreed

that we fill current orders, take our losses and get out of that

business. When I told the PDP-6 group that, they pushed back,

saying, “We think we can build a new computer based on the PDP-6

which will be really super." So I went back to the Works Committee

with a proposal to start a new computer to be called the PDP-10.

After several attempts to get the project approved, we finally

succeeded, and that product became the basis of our very

successful DECsystem-10 and DECSYSTEM-20 families of 36-bit

computers.

Evolution

of the product lines

"Originally, the product lines taught the sales

force about each new product as it came along, and every sales

person sold every product of the company. Then in the late 60s,

some product lines began to feel that their products were getting

so complex that they needed sales specialists. This need was

particularly true with the large computer, the PDP-10. People felt

that it was so big that you couldn't expect a sales person to

understand it technically and also understand all the other

products of the company. So the PDP-10 product line made a big

push to have a specialized sales force concentrating in large

computers, and to a large degree that was accomplished.

"Around the same time, the PDP-8 group

developed a wide variety of applications for their product -- such

as for laboratories, factories, medical departments and schools.

So we began to train the sales force on these applications, At

first, every sales person had to learn about every one of those

applications. Then there started to be some specialization in the

sales force by market.

"Not long after the PDP-11 came out in 1970,

there was some competition between product groups. The PDP-8 group

was pressuring sales people to sell 8s, and the PDP-11 group was

pushing them to sell 11s. We became concerned that our sales

people were confused as to what they should sell to a given

customer. We felt that it was time to specialize our small

computer sales force by market area because small computers were

such an important and growing part of DEC's business and the

number and complexity of applications was also growing. So we kept

the Large Computer Group and the Modules Group as separate

product-oriented product lines, and we broke down our minicomputer

business, the 8s and 11s, into a series of market-oriented product

lines. Many of those — Laboratory, Education, Medical, Industrial

(which we now call Manufacturing) are still in existence today.

"At first the OEM (Original Equipment

Manufacturer) business was a part of the PDP-8 group, of which

Bill Long was the manager. When we divided the PDP-8 group by

markets, Bill became the OEM product line manager. That group

handled both 8s and 11s, as did the other market-oriented product

lines.

'These market-oriented product lines determined

the marketing thrust for the PDP-8 and the PDP-11 in their area,

and would then educate the sales force and the customers as to

which machines were appropriate for which applications.

"That change in the product line structure

raised the Question of what we should do about engineering. People

who were working on PDP-8 and PDP-11 engineering were brought

together into a central engineering organization, under Gordon

Bell, and the Large Computer Group continued to do its own

engineering as a more traditional product-oriented product line.

"I think the whole idea of managing the

business through our product lines was a stroke of genius. I don't

believe we could have ever grown as a company nearly as rapidly as

we did if we hadn't formed product lines, if we'd tried to manage

it as one whole business.

I believe you just can't manage a fast growing,

fast moving organization in detail from the top. It limits the

growth if you try to do it that way. So we've continuously tried

to push decision-making functions down inside the organizations to

product lines, to engineers.

"One of the concepts that hasn't changed from

the beginning of the company is that people are responsible for

the success of the projects they propose. 'He who proposes does.'

When they propose projects and get acceptance, then they go ahead

and carry them out and are Judged on the results. That fundamental

philosophy hasn't changed. I hope it never does.

"But the complexity of things has changed. It's

very easy for a company of our size to get so locked up in bureaucratic

decision-making processes that people feel like they go from

committee to committee making proposals and never getting

anywhere. So we have to keep working to make sure engineers feel

they can propose things and can, once they get acceptance, go out

and do them, that they aren't powerless, that they can get

decisions made.

"One of the thi9ngs you do as a company grows

is try to beat down the hierarchy and the red tape so people can

get their jobs done easily. A lot of what we do, certainly a lot

of what Ken Olsen does, is to tear away the red tape and allow

people to do their jobs. We spend a lot of time trying to make it

fun to work here, make it challenging, make you feel as though you

can make important contributions.

"As for the future, I'd like to see a company

where each individual really feels that he or she has a role to

play and has the freedom to succeed or fail based

on their own ingenuity. One of the horrors of

modern society is 'group-think' or 'group-do,' where you're never

singled out as an individual and don't have an opportunity to show

what you can do all by yourself, based on sour own drive and

ingenuity. I hope 25 years from now we will have a company where

individuals feel challenged and feel that they can really live up to their full

potential.

"My vision of a beautiful company is one where

individuals when they go home at night feel that they really made

an impact, that they've been able to accomplish something, and

they feel proud of themselves and proud of the company they work

for."

Jack

Smith came to DEC in 1958 as a technician. He was involved in

building and testing the company's first logic modules and its

first computer, the PDP-1. Later he was responsible for the

development and growth of the Systems Manufacturing operation.

He was promoted to vice president, Systems Manufacturing, in

1976 and to vice president, manufacturing, in 1977. In 1982 he

took on additional responsibilities as associate head of

Engineering (Photo by Peg Blanchet, U.S. Area News)

"In 1958 when I started at DEC there were only

12 people in the company. I was hired as a technician. Sometimes I

did engineering work. sometimes manufacturing. I also spent a lot

of time painting system modules and sweeping the floor. There

wasn't any formal structure. You Just pitched in and did whatever

had to be done.

"As we grew to around a hundred people, about

I960, we started organizing departments.

"At first we produced one narrow product line —

systems modules, and served one market — the engineering lab area.

So our Manufacturing Department was small and uncomplicated.

Somebody supervised the people putting the product together, and

somebody else was in charge of buying material, and all the

manufacturing disciplines reported to the same manager.

"Then with our first computer, the PDP-1,

manufacturing became much more complex. We had several products

that we were selling to different markets.

"The first few PDP-ls were handcrafted. We had

non-technical people stuffing the modules, but then technicians

and engineers had to take those modules and the frames and plug

them together and wire them, one by one.

"At that time, there was a strong belief in the

industry that you had to understand how a computer operates to put

one were going to get our costs low enough to be successful at

this business, we couldn't afford to have highly paid technicians

and engineers doing assembly work.

"The most complex part of assembling a computer

was stringing the wires. We reasoned that to do a good job of

that, you just have to know which wire goes from where to where.

So we hired non-technical people with basic manufacturing skills.

"At first we had no automated equipment at all.

We simply gave a person a wiring diagram that said, "Take the wire

from point A and bring it over to point Z.“ The person who strung

the wires also had to solder them. Then someone else would go

through and check the work against the diagram, wire by wire, with

over five thousand wires in each computer.

"As it turned out, technical people were not

needed for that kind of work and, in fact, did a far worse job of

it than people with physical dexterity and the ability to pay

attention to detail and concentrate on repetitive tasks.

"Since the product was successful, we had to

hire lots of people to string wires. That also meant we had to

manage and supervise them.

I didn't have any significant role in the

company up until the PDP-l. Then my Job was to supervise the

people who put the machines together and to develop ways to make

sure that they went together right.

"Although my title changed a number of times

and I had various additional responsibilities over the years, up

until I took over as vice president of Manufacturing in 1977, I

was the person responsible for putting together all of the

company's computers, a function that came to be known as ‘systems

manufacturing'.

"We made about forty PDP-1s, which for our

size, was a lot of business. Then we went to the PDP-4, PDP-5,

PDP-6 and PDP-7, still making computers one at a time -- wiring

things together and connecting them.

"The PDP-8, introduced in 1965, was our first

volume computer. We were going to make thousands of them. So to

get the costs low enough to sell them for a low price and open up

new markets, we set up assembly lines. Instead of having three to

five people working on a single computer from start to finish, we

divided the job into a series of separate tasks that different

people could work on at the same time. A computer went through

various stages of assembly, and came out the other end complete.

"With the success of the PDP-8, growth became

the most important issue in manufacturing -- being able to expand our

capacity fast enough to keep up with demand. To speed up growth,

we formed manufacturing groups. Instead of having a single

manufacturing group with a single manager, there was a group

dealing with tape units and another group dealing with central

processors and another group building power supplies.

"To manage all those separate groups, when

there were about 300-1000 people in Manufacturing, we adopted what

is known as 'matrix management.' In other words, we built a strong

central staff, with high levels of expertise in all the various

manufacturing management specialties, such as materials,

production and inventory. These experts were available to help the

individual groups manage their business. For instance, the

materials manager was expected to oversee all the material

functions in all of the individual manufacturing groups. Even

though the materials manager didn't directly supervise the

materials managers in the various operations, that person (the

'matrix manager') was expected to know what was going on in each

one of groups and feel responsible for it.

"We set up this way because we had to grow very

rapidly, and there simply were not enough qualified people, and we

couldn't give people experience fast enough for each group to have

its own set of experts.

"While most manufacturing operations were in

the Mill in Maynard, a matrix manager could easily walk from floor

to floor and talk to people and get things done. Also, back in the

1960s and the early 1970s, the products were mostly based on

modules and central processors, so the different manufacturing

groups faced very much the same kinds of problems and it made

sense to have a strong central staff.

Plants

throughout the world

"In the late 1960s and early 1970s,

manufacturing spread throughout Massachusetts and then the world.

We opened plants in new areas because we couldn't hire enough

people in Maynard.

"When locking for another site in

Massachusetts, we first chose Westminster because we wanted to be

as close to Maynard as possible and still tap a significant new

labor supply. Westfield was the next step beyond that, and so on.

"When we started a new plant, we would send out

a team -- typically about five people -- from one of our existing

plants. Everyone else was hired locally.

"Often the plan was to get 50-75 people in the

first year, and by the end of the second year to have 400 people,

all used to the DEC way of doing things. After that was done, then

they could worry about questions of further growth. That was the

pattern not only in the U.S., but also in Canada, Puerto Rico and

Europe.

"But as we spread out geographically,

communication with matrix managers back in Maynard became

increasingly difficult. Also, as we got into new businesses, like

printers and terminals and disks, manufacturing operations became

diverse, requiring different kinds of expertise. At the same time

the need for increased volume intensified. Gradually, central

control became more of a hindrance than a help.

"A matrix organization gives you the ability to

grow rapidly with a limited number of experienced managers, but it

also tends to make responsibility fuzzy and to make decision paths

very long. Who is really responsible? Is it the line manager or

the matrix manager?

“By 1977 matrix management had outlived its

usefulness; so we reorganized Manufacturing into standalone groups

that were responsible for their own products.

"Up

until then we had one group producing all the modules for

everyone, another producing power supplies for everyone. We

divided and shifted those resources so, for instance, Storage

Systems could make its own modules and its own power supplies, do

its own assembly work, its own testing, its own systems work. It

took a few years to arrive at the point that each group had under

its own control the capacity it needed to get its job done.

"Meanwhile, during the rapid growth of the

1960s and 1970s, each of the company's organizations, such as

Engineering and Manufacturing were structured and chartered to

operate independently. There was very little interaction between

Manufacturing and the rest of the company when it came to choosing

plant sites or making other decisions, and there was no formal

process for deciding how much of what product we should build.

That was a good thing when the main goal was to grow as fast as

possible. But now there is more benefit to be gained from working

efficiently and doing what we need to do to win now. So the

emphasis has shifted toward close cooperation between the various

parts of the company.

"For the future, I believe that we have to

continue to reinforce our strong standalone manufacturing groups.

They have to build their own capacities to the point that they

feel they control and are responsible for their own destiny. We're

still shifting capacity to help reach that goal.

"Our basic strength has always been the

attitude and commitment of our people. I think the most important

thing Manufacturing can do is to continue to provide challenging

opportunities for personal and professional growth while we

reinforce our commitment to achieve manufacturing leadership in

our industry."

Jack

Shields joined DEC in 1961 and was named manager of Field

Service in 1964. He was promoted to vice president, Field

Service and Training in 1974 and vice president, Sales, Services

and International in 1981. (Photo by Peg Blanchet U.S. Area

News)

’If you think about what's happened in computer

technology in the last 25 years, it's like future shock. Each year

more and more events take place which bring us further into the

technological future. If you think of the millions of years man

has been on earth, 25 is so short a time it's almost not worth

talking about. But in that time incredible progress has been made

in the field of computers that has had far-reaching effects on

many aspects of life — from education and entertainment to

medicine and space travel. A lot of this has been captured in the

Digital Computer Museum. It's been exciting to live in the time of

these developments as well as participate in some of them.

"Twenty-one years ago when I started at DEC, I

was twenty-one years old. The company was young too; it had only

shipped two computer systems. There was a PDP-1 at Bolt, Beranek

and Newman and another at the Itek Corporation. Then in August or

September, 1961, we delivered the third to MIT.

"I worked in Engineering, but back then, with

less than a hundred employees in the whole company, the few dozen

of us in Engineering did a bit of everything. Maybe you'd work on

design one day and test the next, and then you might be called on

to do installation or servicing. People in Manufacturing helped

out in Engineering and vice versa. It was a closely knit group,

and everybody wore a lot of hats.

In fact, the only functional differentiation was based on

who you worked for.

"As it turned out, I and a few others ended up handling more service

calls than the rest of the people did. After a while our names

naturally came up when customers called needing help.

"So when someone was hired to set up a training

and field service facility, I was asked to So on loan for three

months to set up the service organization. At the end of the three

months, I was asked to stay in the Job. So Bill Newell and I

started and developed the DEC Field Service organization.

"We installed and maintained the equipment,

designed and built our own logistics system, and developed

techniques for handling calls. From time to time, we would have

our trainees work in Manufacturing so they could get on-the-Job

training while helping to test and build the products and get them

shipped on time.

Jack Smith used to run a piece of

Manufacturing. He and I sometimes had to get together to work out

shipment schedules because the service organization couldn't

handle all the products he could build and ship, or because he

needed some help from my people to get more systems tested. Once

the systems were tested, manufacturing people would go out with us

in the field and help install them. Then, having given the

manufacturing people a taste of the field life, it was easier to

recruit some of them. All in all, the reciprocity was great, and

our size made it much easier to work together on common company

goals.

"The organization became international around

1963. Ted Johnson transferred from California to Germany, and our

first Canadian sales office opened that year. I remember having

booth duty with Ted at a trade show in Basle, Switzerland, showing

the PDP-4. That was my first business trip to Europe.

"We were primarily selling modules and logic

kits, and then we started to sell our computers and memory

testers. Customers were more sophisticated then than they are

today, but they still required support.

"Originally, we hired local people for service

in Europe. Then we transferred Ken Senior to run our European

Field Service organization out of the United Kingdom. As I recall,

in 1964 we had about 11 field service people in Europe.

“Today we have nearly 20,000 people in Customer

Services worldwide, and everything is highly specialized to reduce

cost per repair arid increase productivity. We have specialists

for call handling. We do a lot of remote diagnosis. But in the

early days of DEC, the technician in the field had to be a

generalist, able to handle all aspects of diagnosis arid repair of

hardware and software. Many times you didn't have all the modules

with you, but you did have the components, so you would

trouble-shoot and repair down to capacitor and transistor level.

(Today those components are buried -- tens of thousands of them on

a single integrated circuit --

and you can't get at them.)

"Back then you had relatively few diagnostics

to work with, and they were relatively unsophisticated. Generally,

it was a customer's program that failed, and you had to figure out

what that program was doing and trace the problem from there. A

lot of the programming was done in machine language rather than in

higher level languages, and the programs you would use to exercise

the product were written by the customers. Our techniques for

checking the circuitry were marginal. We would vary the voltages

applied to the various gates to try to induce or reproduce the

failure. Also we had to cope with a lot of design problems that

couldn't be eliminated because testing was nowhere near as

sophisticated as today.

"To me the tremendous growth of DEC over the

last 25 years presented experiences that I don't think many people

will ever have again. You needed technical skills and had to keep

those finely honed, and at the same time you had to build an

organization and therefore develop the people and organizational

skills which were required, and then add to that the business

skills and the ability to create a new function and a new way of

providing a service. I'm extremely grateful for the opportunity to

face those challenges and to grow. Personally, it's been an

incredibly rewarding and rich experience.

"Quietly, without a lot of fanfare, DEC changed

the way companies view service. We took an activity that companies

had always thought of as a nuisance and a problem, a necessary

evil, and we made it into a profitable business. We started

showing a profit way back in the early 60s, and over the years we

were able not only to provide high quality service, but also to

develop new techniques which allowed us to become more productive

and cost effective and pass those savings on to our customers. We

created a new way of approaching service that today the rest of

the computer industry is trying to emulate.

We have done similar things in Educational

Services and Software Services, in parallel with the company

growing, the technology changing, and our people maturing.

"To me the most remarkable thing is the

stability of the services organization over the years. I recently

looked at a memo that was written in 1964. It listed the 35 or so

people who were in Field Service at that time. There are 20 of

them who are still with DEC today. I think that speaks for the

stability, the commitment and the performance of the organization.

"From a business performance point of view,

it's been an unprecedented success story. We continue to meet or

exceed our fiscal goals for the twentieth successive year, and in

the Just completed annual customer opinion survey -- the real test

of our performance -- the improvements were dramatic. On a scale

of 1 to 10, we're well above 8 on average. No other company that I

am aware of can point to that kind of balanced performance.

"The future looks even more promising. The

Software Services organization is a tremendous asset that will not

only provide a source of revenue but a tremendous competitive

advantage for DEC well into the 90s. Educational Services has

tremendous areas of untapped potential. For instance, the latest

computer-interactive video disk technology that they developed

with our Small Systems Group (IMIS) and the courseware that goes

with it will put us in a leadership position in computer-aided

instruction. The Field Service organization will continue to

innovate, continue to find new methods, new services and new

sources of revenue. I'm betting that they'll continue to be the

best in the industry, and they'll still grow at an unprecedented

rate."

seltzer@seltzerbooks.com

privacy

statement