Richard Seltzer's

home page Publishing home

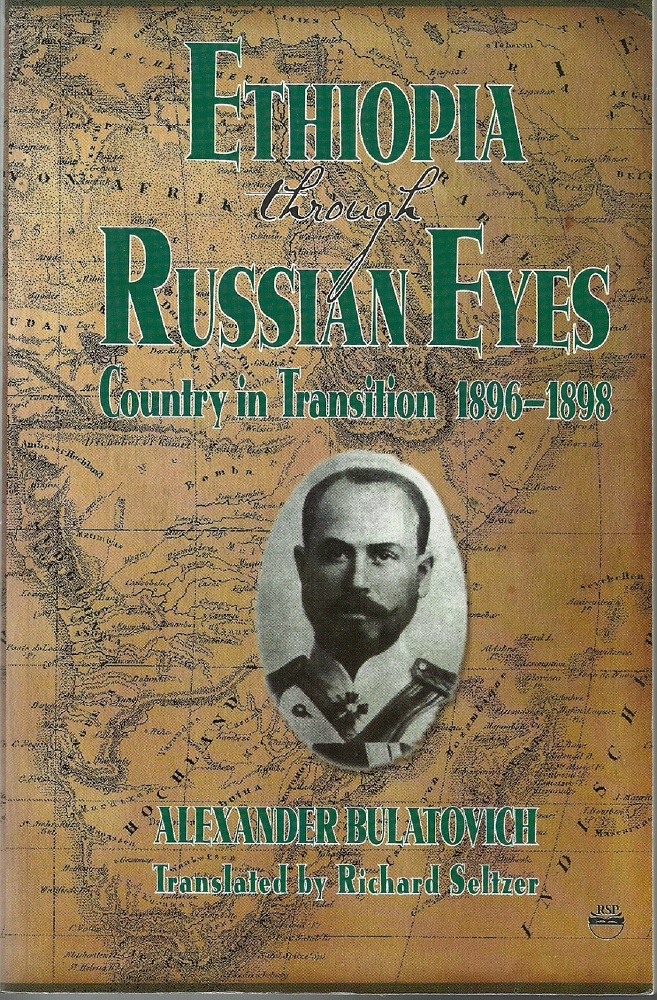

ETHIOPIA THROUGH RUSSIAN EYES, COUNTRY IN TRANSITION 1896-1898

Second edition, revised and expanded, with

the original photographs, 2020

Two books by Alexander Bulatovich, translated

by Richard Seltzer

Translation copyright 1993 Richard Seltzer

Print edition published 2000 by The Red Sea

Press, 11-D Princess Road, Lawrenceville, NJ 08648, PO Box 48,

Asmara, Eritrea

Ebook published by Seltzer Books

established in 1974, as B&R

Samizdat Express

feedback welcome:

seltzer@seltzerbooks.com

A review of this book in "Old Africa"

begins: "Despite its bland title, this is the most

important book on the history of eastern Africa to have been

published for a century. And it was written over a century ago!

... Based on

Bulatovich's day-to-day diary, it is not only the sole but a

vivid first-hand description of how Menelik II created his

Ethiopian Empire." Complete

text of that review.

A related book by Bulatovich, also translated

by Richard Seltzer is also available for free at this web site.

My Third

Journey to Ethiopia, 1899-1900.

Richard Seltzer's historical novel The Name of Hero is

based on the life of Alexander Bulatovich. It is available on the

web and also as an ebook at Kobo and at Nook (Barnes &

Noble).

Sources and related documents are available

on the Web.

A. X. BULATOVICH

-- HUSSAR, EXPLORER, MONK BY KATSNELSON

FOOTNOTES TO A. X. BULATOVICH -- HUSSAR, EXPLORER, MONK BY

KATSNELSON

FROM ENTOTTO TO THE

RIVER BARO BY ALEXANDER BULATOVICH

WITH

THE ARMIES OF MENELIK II BY ALEXANDER BULATOVICH, TRANSLATED

BY RICHARD SELTZER

TIMELINE FOR ALEXANDER

BULATOVICH

EMAIL FROM DR. GIRMA IYASSU,

GREAT-GREAT GRANDSON OF MENELIK II -- NEWS OF VASKA

TRANSLATOR'S

INTRODUCTION

A young Russian cavalry officer witnessed as

Ethiopia vied with Italy, France, and England for control of

previously unexplored territory in east-central Africa. His two

books are an important source of historical and ethnographic

information about that little-known but critical and exciting

period.

Almost all official Ethiopian documents from

the 1890s were destroyed during the war with Italy in 1936. The

historical record depends largely on the observations of

European explorers and visitors, of whom Alexander Bulatovich

was one of the very best. The books included here cover the

first two (1896-97 and 1897-98) of his four trips to Ethiopia.

Bulatovich sensed that Ethiopia was in a

delicate state of transition, that what he was seeing would not

remain or even be remembered in a generation or two. He had the

instincts, although not the training, of an anthropologist,

trying to preserve some record of fast-disappearing cultures.

But he was not a scientist who observed with cool detachment.

Rather, he was actively involved in the events he described,

particularly on the expedition to Lake Rudolf. He became

ambivalent, torn by his military duty (as an officer attached to

the army of Ras Wolda Giyorgis) and by his personal values and

sense of justice. Time and again, he found himself party to the

decimation of the very people whose culture he wanted to

preserve.

He approached his subject with enthusiasm,

fascination, and, at times, with almost religious respect. He

did not presume that European culture and technology were

morally superior. Nor did he romantically prefer the

"primitive."

Empathizing with many of the peoples he

encountered, he witnessed the tragedy of the clash between

traditional ways and modern arms. He considered modernization

inevitable, but preferred that it be done in the most humane

manner. Hence he considered conquest and gradual change under

the Amharic rulers of Ethiopia as preferable to the total

destruction which would be likely in case of conquest by a

European power.

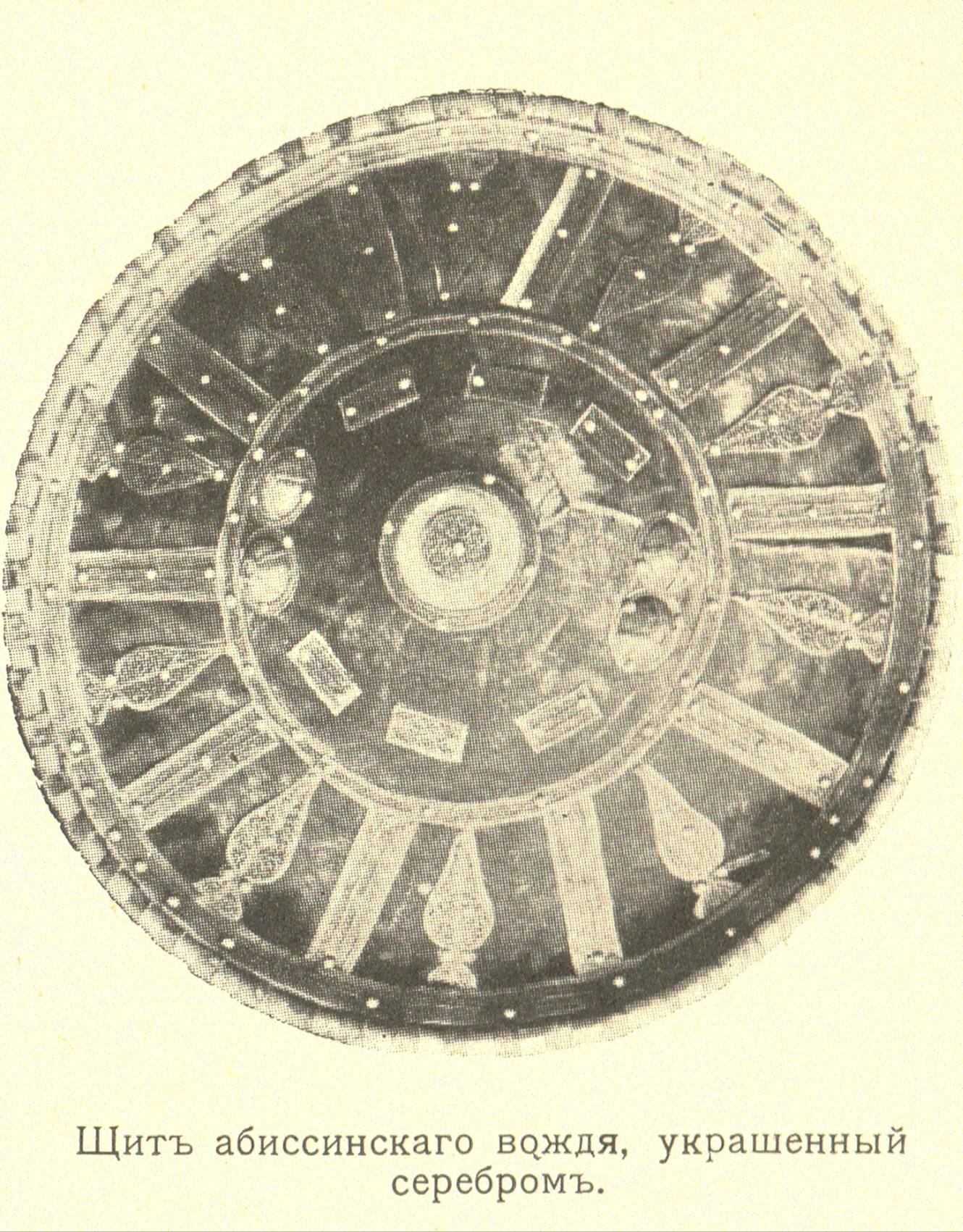

Bulatovich had a strong natural interest in

military and religious matters, and that was at the heart of his

respect for these people. He saw the Abyssinian military as

having recently passed through a golden age of cavalry charges

and individual heroism, which called to mind the by-gone days of

medieval Europe. He saw the Ethiopian Church as close to the

Russian Orthodox Church and the origins of Christianity, and he

greatly respected all the details of their belief and practice,

and all their unique legends and saints.

He was, however, a product of his time: the

time of Kipling and the Berlin Conference. In those days, it was

common for Europeans to make judgements about cultures, based on

a scale in which their own culture was at the top. He shows

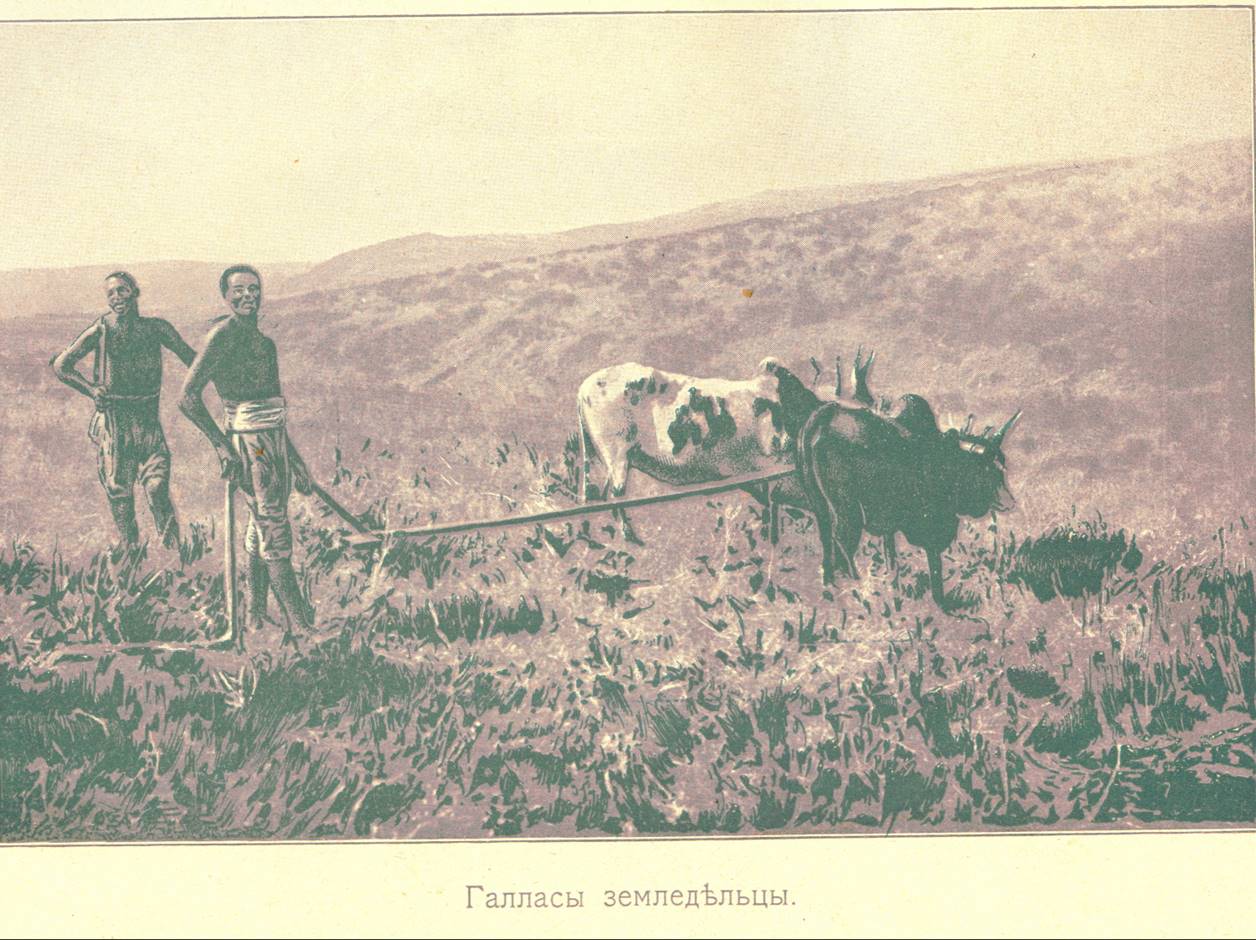

great respect for and understanding of Amhara, Galla (Oromo),

and several other Ethiopian peoples and cultures, with whom he

had prolonged contact and whose languages he learned. But he

uses strong negative terms to describe the people and cultures

of what is now Southern Ethiopia. In part, this prejudice is due

to ignorance -- he had little contact with these people and did

not understand their language. In part, too, it was a reflection

of the attitudes of his comrades-in-arms -- Amhara and Galla

warriors -- who also were encountering these people for the

first time, and for whom they were just as foreign and

incomprehensible as they were to Bulatovich.

His works should appeal to anyone interested

in the history or anthropology of Africa and Ethiopia. They also

provide a clear picture of the relations between Russia and

Ethiopia in the 1890s, which planted the seeds of their

present-day relations. And these accounts can help fill in

historical details regarding events and individuals during that

era, and can serve as a valuable resource to specialists.

________________________________________

Up until now, the main source in English

about Russian activities in Ethiopia and their observations of

that country has been The Russians in Ethiopia: An Essay in

Futility by Czeslaw Jesman. This is an amusing collection

of rumors and anecdotes, based primarily on Italian sources.

Unfortunately, it is often wrong; but, in the absence of a

better source, its errors have often been repeated.

One speech which Bulatovich made to the

Russian Geographical Society was translated into Italian and

French and is frequently cited. But his two books, up until now,

were available only in Russian. Hence his observations and

contributions have remained virtually unknown in the West.

Bulatovich's first book, From Entotto to

the River Baro, published in 1897, consists of journals of

two excursions he went on during his first trip to Ethiopia

1896-97, plus a series of essays based on what he heard and

observed during his year-long stay with the Russian Red Cross

Mission. The essays deal with various peoples of Ethiopia

(Galla/Oromo, Sidamo, Amhara) -- their history, culture, way of

life, beliefs and languages; on the governmental system and its

historical background, on the army, on commerce, and on the

Emperor's family.

With the Armies of Menelik II,

published in 1900, is the journal of Bulatovich's second trip to

Ethiopia 1897-98, during which he served as an advisor to the

army of Ras Wolda Giyorgis as it conquered the previously

little-known southwestern territories from Kaffa to Lake Rudolf.

Here he builds on his previous knowledge of the country and also

recounts an exciting personal story of military adventure, which

builds to a climax in the final chapters.

Both books, edited and with an introduction

by Isidor Savvich Katsnelson, were reissued by The Institute of

Oriental Studies in Moscow in 1971.

________________________________________

I first discovered Bulatovich in the London

Times of 1913, while looking for another story, on which I

wished to base a novel. The article described how Russian troops

had besieged two monasteries at Mount Athos in Greece and exiled

some 660 monks to remote parts of the Russian Empire for

believing that "The Name of God was a part of God and,

therefore, in itself divine." Bulatovich -- a former cavalry

officer who had "fought in the Italo-Abyssinian campaign, and

afterwards in the Far East" -- was the leader and defender of

the monks. ("Heresy at Mount Athos: a Soldier Monk and the Holy

Synod," June 19, 1913).

News was a more leisurely business then than

now. The reporter drew an analogy to characters in a novel by

Anatole France and drew an interesting sketch of the background

and motivations of the main figure. I got the impression of

Bulatovich as a restless man, full of energy, chasing from one

end of the world to the other in search of the meaning of life.

Eventually, he sought tranquility as a monk at Mount Athos, only

to find himself in a battle of another kind.

I was hooked by this new character and new

story. What would a Russian soldier have been doing in Ethiopia

at the turn of the century? What war could he have fought in the

the Far East? What was it that compelled him to go from one end

of the world to the other, and then to become a monk?

After getting out of the Army, I moved to

Boston, where my future wife, Barbara lived. There I tracked

down all available leads to this story, but could find very

little additional information. There was a poem by Mandelshtam

about the heresy. The philosopher Berdyayev had nearly been sent

to Siberia for expressing support for the heretics. But that was

it.

Then in the spring of 1972, the "B" volume of

the new edition of the official Soviet Encyclopedia (Bolshaya

Sovietskaya Entsiklopedia) appeared. The previous edition had

mentioned an "Alexander" Bulatovich who died about 1910. The

Bulatovich in the Times article was named "Anthony" and was very

much alive in 1913. The new edition made it clear that Alexander

and Anthony were the same man. (In the Russian Orthodox Church,

when becoming a monk, it is common to adopt a new name with the

same first letter.) The new article corrected the date of his

death (1919) and referenced books that Bulatovich had written

about his experiences in Ethiopia. This encyclopedia item was

signed by Professor I.S. Katsnelson, from the Institute of

Oriental Studies, in Moscow.

I wrote to Professor Katsnelson, and to my

delight, in his reply, he sent me a copy of a recently published

reprint of Bulatovich's Ethiopian books, which he had edited,

and also gave me the name and address of Bulatovich's sister,

Princess Mary Orbeliani, who was then 98, and living in Canada.

Katsnelson offered to help me gain access to

Soviet archives that had some of Bulatovich's unpublished notes

and other related materials. But my Army security clearance

prevented me from travel behind the Iron Curtain. (I was then in

the Army reserves.)

Instead, in the summer of 1972, I traveled to

Mount Athos, where I spent two weeks, mostly doing research in

the library of St. Pantelaimon, the one remaining Russian

monastery there.

Meanwhile, I corresponded with Princess

Orbeliani, and visited her for two days the following summer in

Penticton, British Columbia. In long tape-recorded conversations

and in letters before and after that visit, she provided me with

valuable information about her brother's life and insight into

his character. At 99, she was very articulate, lucid, and

helpful. She was delighted that someone was showing an interest

in her brother's work and beliefs. She was a remarkable and

inspiring person -- unassuming, warm and open. Living in a

nursing home, she continued to pursue her artwork, specializing

in water colors. Although her fingers were swollen from

arthritis and she had difficulty even unwrapping a piece of

candy, she could still play Chopin on the piano from memory,

smoothly and without hesitation. Her own tale would make an

interesting book: flight during the Revolution by way of Baku to

Yugoslavia, and hardship there under the Nazis; sending her son

to engineering school in Louvain, Belgium; his career in the

Belgian Congo; and then eventually joining him in British

Columbia. (She passed away in 1977 at the age of 103).

Increasingly, I was getting caught up in the

research, carrying it far beyond what one would normally do to

write an "historical novel." Each new piece of information

raised more questions and pulled me in even deeper.

At Harvard's Widener Library, I was able to

follow up references and find related materials. In this manner,

I found and photocopied numerous books and articles about

Ethiopia, as well as the heresy, and the Manchurian campaign of

1900.

I was fascinated by Bulatovich's character

and wanted to work out the puzzle of his motivations, and what

might have led to the shifts and twists of his life: from St.

Petersburg, to Ethiopia, to Manchuria, then back to St.

Petersburg where he became a monk, and on to Mount Athos,

becoming the champion of the "heretics" there, then a chaplain

at the Eastern Front in World War I, surviving the Revolution

and Civil War, and returning to preach on what had been his

family's estate in the Ukraine, only to be murdered by bandits.

What drove him to do the things he did? How

could I present all these facts I had uncovered in a way that

they seemed plausible?

Eventually, I wrote The Name of Hero.

Intended as the first part of a trilogy, this novel focuses on

Manchuria, with flashbacks to his childhood and to Ethiopia.

Professor Katsnelson died in 1981, the year that Hero was

published.

Katsnelson (1910-1981) was a professor at

Institute of Oriental Studies of the Academy of Sciences of the

U.S.S.R., in Moscow. He was a specialist in ancient Egypt and

Nubia, best known for his monograph Napata and Meroe -- the

Ancient Kingdom of Sudan published in 1971. He had a personal

interest in Ethiopia and Bulatovich in particular. In 1975,

together with G. Terekhova, he published a popularized biography

of Bulatovich entitled Through Unknown Lands of Ethiopia. He

also edited and, in 1979, published a book by another Russian

explorer of Ethiopia, a contemporary of Bulatovich, L.K.

Artamanov, entitled Through Ethiopia to the Banks of the White

Nile. Katsnelson also uncovered in the Soviet Archives a series

of previously unpublished documents by and about Bulatovich in

Ethiopia. These were eventually published in Moscow in 1987 as

Third Expedition in Ethiopia by Bulatovich. Selections from his

introduction to the first Bulatovich books, with unique

biographical details about Bulatovich, are included at the end

of this volume.

While I was researching my novel, I

translated portions of Bulatovich's Ethiopian books for my own

use. The more I read about Ethiopia, the more it became clear to

me that experts in the field were unfamiliar with these works

and could benefit from them, and also that they contain much

that would interest the general reader and lover of history.

Finally, with the prompting of Professor Harold Marcus of

Michigan State University, I made the time to translate both

books in full. I am now writing the next Bulatovich novel.

________________________________________

TRANSLATION NOTES

Up until the Revolution, Russia used the

Julian or "old style" calendar, which, in 1897-98 lagged 12 days

behind the Gregorian calendar, which was used by the rest of the

world. Since Bulatovich used the "old style" and celebrated

religious holidays, such as Christmas, in accord with that

calendar, his usage has been retained in this translation.

I have not anglicized the names -- except

Biblic ones in a church or historical context (e.g. the Queen of

Sheba), and Bulatovich's middle name Xavieryevich (instead of

Ksaveryevich), to indicate the Roman Catholic origins of his

father, Xavier.

Ethiopian words in the text pose a particular

problem. Bulatovich used non-traditional phonetic methods to

render what he heard into Cyrillic characters. Strictly

following standard Cyrillic-to-English transliteration practice

would lead to unnecessary confusion, making it difficult to

recognize when he is writing about well-known historical people,

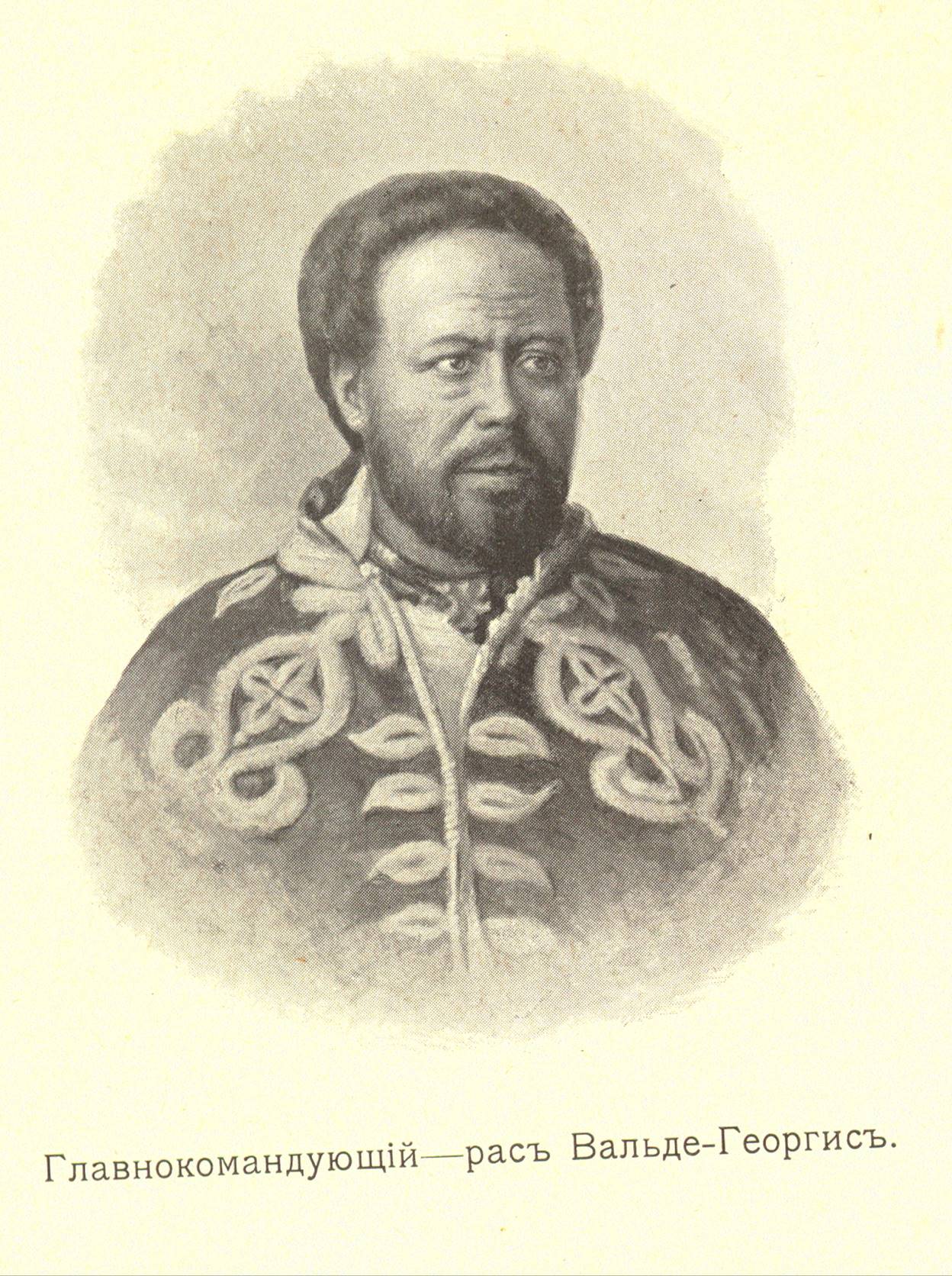

places, and events. For instance, the general he accompanied on

the expedition to Lake Rudolph is commonly rendered in English

as Wolda Giyorgis, but direct transliteration from Bulatovich's

Cyrillic would yield Val'dye Gyeorgyis. And the common title

dajazmatch in direct transliteration would have been dadiazmach.

To avoid this problem, where the Amharic

original is obvious and the person, place, or thing is

well-known, I follow the spelling in The Life and Times of

Menelik II by Harold G. Marcus.

In other cases, I deviate from standard

transliteration to yield spellings consistent with well-known

ones. For instance, the Russian letter "U" at the beginning of a

word and before a vowel is rendered "W" in this text (as in

Wollo and Wollaga). Also, the Russian character that is normally

rendered with the two-letter combination "kh" is transcribed

here simply as "h" when it falls at the beginning of a word (as

in Haile). And the combination of two Russian letters -- "d" and

the letter normally rendered as "zh" -- is here treated as the

single letter "j" (as in Djibouti and Joti). Also, the series of

titles ending in -match, such as dajazmatch, are rendered

consistently with "tch" rather than just "ch" as in Bulatovich's

usage.

For convenience, when Bulatovich uses Russian

units of measure for distance (verst), length (vershok, arshin,

sagene), temperature (Reamur), weight (pood), I provide a direct

translation and immediately follow with the conversion to common

American units of measure [in brackets].

The paragraph breaks are the same as in the

original (for easy comparison of one text with the other).

Ellipses (...) are used here the same as in

the original. They do not indicate that material has been

omitted.

Thanks to the dozens of people from the

Internet newsgroups soc.culture.soviet and k12.lang.russian who

took the time to help me decipher obscure and obsolete Russian

terms and identify literary quotations. Alexander Chaihorsky

deserves special thanks for his insight into the meaning of

"sal'nik" based on his experience as an explorer in northern

Mongolia. Thanks also to another Internet contact: Zemen

Lebne-Dengel, who explained for me the Amharic words t'ef and

dagussa.

A. X.

BULATOVICH -- HUSSAR, EXPLORER, MONK BY ISIDOR SAAVICH

KATSNELSON

The

introduction to Katsnelson's edition of Bulatovich's Ethiopian

books -- With the Armies of Menelik II, edited by I.

S. Katsnelson of the Institute of Oriental Studies of the

Academy of Sciences of the U.S.S.R."Science" Publishing House

Chief Editorial Staff of Oriental Literature Moscow 1971.

translated

by Richard Seltzer, seltzer@seltzerbooks.com

[Numbers

refer to footnotes at the end of this essay.]

Africa

has hidden and still hides much that is unknown, unexplored,

enigmatic. Even today there are regions of Africa where the

foot of an explorer has never trod. Kaffa (now one of the

provinces of Ethiopia) remained a legendary country up until

the very end of the last century -- "African Tibet" -- having

fenced itself off from the outside world. Foreigners were

strictly forbidden access to this country. Even now, we know

less about it, its history, morals, customs, and the language

of the inhabitants and the neighboring tribes to the south and

west than about any other region of Ethiopia. The first

traveler and explorer who crossed Kaffa from end to end and

compiled a detailed description of it was the Russian officer

Alexander Xavieryevich Bulatovich.

The

life path of A. X. Bulatovich was truly unusual. Having begun

in one of the most exclusive educational institutions of

tsarist Russia and in the fashionable salons of Petersburg, in

the circle of brilliant guard officers, he dashes across

deserts, mountains, and plains of the least known regions of

Ethiopia; across the fields of battle and hills of Manchuria;

a solitary monastic cell and monasteries of Mount Athos

embroiled in fanatic scholastic arguments; across First World

War trenches soaked with blood, saturated with stench; and

tragically, senselessly comes to an abrupt end in a little

hamlet in the Ukraine.

The

posthumous fate of A. X. Bulatovich was no less amazing.

At

the very end of the last century and before the First World

War, he repeatedly found himself at the center of attention of

the Russian, and, at times, also of the foreign press. But

then he was completely forgotten.

To a

considerable extent, the cause of this was the October

Revolution and events of succeeding years. But, however it

came about, up until recent times almost nothing was known

about A. X. Bulatovich. Even the year of his death given in

the second edition of the Big Soviet Encyclopedia -- "around

1910" -- was incorrect.(1) His discoveries and observations

did not receive full appreciation. In any case, no one who

wrote about him indicated that he was in fact the first man to

cross Kaffa.(2)

Only

now, when searches have been begun in the archives and some

people who knew A. X. Bulatovich or were related to him have

responded, (3) his image has become more distinct and the

great significance of his journeys and of his scientific work

is becoming clearer.

However,

this research is still far from complete. Much apparently

needs to be amplified, and also, possibly to be made more

accurate. For instance, we now know almost nothing about the

last three to four years of his life, and the circumstances of

his death are known only in the most general way. We will try

here to sum up briefly all that we have learned about him in

recent years.

A.

X. Bulatovich was born September 26, 1870 in the city of

Orel.(4) At that time, the 143rd Dorogobuzhskiy Regiment,

which was stationed there, was commanded by his father,

Major-General Xavier Vikentyevich Bulatovich, who was

descended from hereditary nobles of Grodno Province. X.V.

Bulatovich died around 1873, leaving a young widow, Evgeniya

Andreyevna, with three children.

The

childhood years of Alexander Xavieryevich and his two sisters

were spent at their wealthy estate known as "Lutsikovka" in

Markovskaya Volost, Lebedinskiy District, Kharkov Province.(5)

Already at that time some traits of his character and world

view took shape: courage, persistence, passionate love for his

native land, and deep religious piety.

In

1884, Evgeniya Andreyevna moved with the children to

Petersburg. It had come time to send them to school. The girls

entered the Smolny Institute. The elder daughter soon died of

typhus. A. X. Bulatovich, who was then 14, began to attend the

preparatory classes of the Alexandrovskiy Lyceum -- one of the

most exclusive educational institutions. (6)

Having

passed the entrance examinations, A. X. Bulatovich was

admitted to the Lyceum. His only difficulty on the exam,

strange as it may seem, was in geography, which he just barely

passed. Subsequently -- right up to graduation -- he studied

excellently, advancing with prizes from class to class.(7)

Future diplomats and high government officials received their

preparation at this Lyceum. Therefore, the pupils mainly

studied foreign languages -- French, English, and German --

and jurisprudence. In other words, A. X. Bulatovich received

an education in the humanities, but that didn't prevent him

from becoming a capable mathematician, as indicated by the

geodesic and cartographic surveys he conducted.

In

1891 A. X. Bulatovich finished the Alexandrovskiy Lyceum as

one of the best students and went to work in May of that same

year in "His Majesty's Personal Office in the Department of

Institutions of the Empress Mary," which directed educational

and beneficial institutions. He was awarded the rank of the

ninth class, which is "titular councilor." (8) However, a

civil career did not entice him; and following the family

tradition, he submitted an application and enlisted on May 28,

1891 as a "private with the rights of having volunteered" in

the Life-Guard Hussar Regiment of the Second Cavalry Division,

(9) which was one of the most aristocratic regiments. Only a

select few could become officers of such a regiment.

After

a year and three months, August 16, 1892, A. X. Bulatovich

received his first officer's rank -- cornet. (10) After

another year, he made his way onto the fencing team, formed

under the command of the Horse Grenadier Guard Regiment, with

the task of becoming a fencing instructor. He stayed there for

a half-year, then on April 10, 1894, was sent back to his

regiment, where he was first appointed assistant to the head,

and then, on December 24, 1895, head of the regimental

training detachment.

Although

A. X. Bulatovich was taught in a civil educational

institution, he acquired riding skills in childhood and youth;

and through persistent training at riding school and at race

courses, he became an excellent horseman -- possibly one of

the best of that time. That was not an easy accomplishment:

Russian cavalry and Cossack regiments always had a reputation

as first-class horsemen. According to trainer I.S. Gatash, who

served in the stable of A. X. Bulatovich, (quoted by V.A.

Borisov who found the old man), "For Alexander Xavieryevich,

the horse he couldn't tame didn't exist."

Thus,

interrupted only by races and other horse competitions, the

years of service in the regiment passed rather quietly, until

events which at first glance did not have any relation to A.

X. Bulatovich suddenly broke the settled tenor of life of the

capable, prospering officer.

At

the end of the nineteenth century the colonial division of

Africa among England, France, Germany, Spain, and Portugal was

completed. Only Ethiopia had preserved its independence,

together with the almost unexplored regions adjacent to it on

the south and southwest, plus some difficult-to-reach regions

of the central part of the continent. Italy, which had joined

in the division of Africa later than the other European

imperialistic powers, felt that it had been done out of its

fair share. Only at the end of the 1880s did it settle in

Somalia and Eritrea. Now, according to the plan of its leading

circles, should come the turn of neighboring Ethiopia.

In

Ethiopia itself and around it at this time arose a very

complex situation -- a true Gordian knot of conflicts,

interlaced from the struggles of the colonizing powers, with

unavoidable diplomatic intrigues, threats, briberies, lying

promises and punitive expeditions. The ruling empeor,

king of kings of Ethiopia -- Menelik II, continuing the

efforts of his immediate predecessors, secured the unification

of previously fragmented independent

and half-independent principalities into a single centralized

state that in the given concrete circumstances undoubtedly had

led to progress and had answered the aspirations of various

sections of the population and, above all, of the governing class. Those

close to Menelik II hoped to get lucrative and esteemed posts

and appointments, with associated revenue; and merchants and

artisans hoped to be able to safely conduct their business,

without fear of the constant civil strife which the peasants

were subject to. The reforms carried out by the Negus

benefitted the economic development of the country. The

penetration of foreign capital and the invitation of various

specialists from Europe -- basically engineers to improve

roads and repair communications -- and also the establishment

of a single monetary system, to a significant degree, helped

make that happen. For the first time in the history of feudal

Ethioipia, there arose relations characteristic of the

beginning stage of capitalist society.(11) It was natural that

the strengthening of Ethiopia did not was not welcomed by

those who were striving to take control of this country,

considering its key position on strategic lines of

communication, and the fact that it was liberally endowed by

nature and offered vast opportunities for the sale of

industrial products. England and Italy acted actively and

purposefully. England strove at this time to realize plans

that it had not up until then been able to carry out -- to

seize the regions of Central Africa that separated its colony

in Uganda from the Sudan, which it controlled, and thus to

unite all the possessions and zones of influence from the

Mediterannean Sea to the Cape of Good Hope. The realization of

those plans would naturally help establish reliable lines of

communication. They wanted to stretch telegraph wires from

Capetown to Cairo through the nominally independent Congo

which by decree of Germany refused to give permission for this

work.

From

Mombassa on the shores of the Indian Ocean, they intended to

extend a railroad line past Lake Victoria and Lake Albert to

Khartoum.(12) But on that path lay Ethiopia, which had

preserved in full measure its independence and which was not

at all interested in this railroad line. This is why England,

having tried to take possession of the western regions of

Ethiopia necessary for building that railroad line and having

tried to penetrate neighboring areas, not only did not stand

in the way of the aggressive intentions of Italy, but even

encouraged them,(13) having signed with them in 1891 two

protocols (March 24 and April 15) about the demarcation of

spheres of influence in countries adjacent to the Red Sea. The

protocol of May 5, 1894, recognized the predominance of the

interests of Italy in Harar, where the penetration of France

was making matters difficult. France was a stronger colonial

power with which it would be far more difficult to come to an

understanding. A significant part of Ethiopia, according to

this predatory secret deal, would go to Italy,(14) which

England by all means strove to keep out of the Sudan. By the

terms of this deal, the sphere of influence of the Italians

included the western lands bordering Ethiopia that were

populated by the Sidamo people, although the English

themselves showed far from platonic interests in that

territory.

Having

negotiated with England, Italy stirred up its own political

action in Ethiopia, to which they sent a supposedly scientific

expenditions, consisting solely of active dutry officers. Such

were, for example, two expeditions of artillery officer V.

Bottego.(15) However, as you can easily conclude from reading

the work and the reports of A. K. Bulatovich, neither the

Italians nor the English succeeded in gaining control of that

territory.(16)

The

attempts of Italy to make Ethoipia a protectorate were

unsuccessful. Then, throwing off the mask of sham friendship,

Italy turned to open aggression and in July 1894 occupied

Kassala, by this act starting the Italo-Abyssinian War,

disgracefully ending with the crushing defeat of Italy at Adwa

on March 1, 1896.(17) This brilliant victory had important

consequences for Ethiopia. Above all, the victors obtained

valuable trophies, of which the most important were up-to-date

weapons: a large quantity of rifles and cartridges, all kinds

of artillery with a large quantity of ammunition and all kinds

of transport.(18)

The

victory at Adwa played a major role in the history of

Ethiopia. It not only united its indigenous population, but

also to a great degree helped strengthen and unify this feudal

state, significantly strengthening its international

authority. Its military power increased. Ethiopia, by its very

existence, first demonstrated to the imperial powers that the

people of Africa can stand up for their independence and have

right for independence existence. This historical lesson had

lasting importance in the struggle of African peoples against

colonial oppression, as Bulatovich realized very well when he

wrote,"... Menelik engaged with Italy in a desperate struggle

for the existence of his state, its freedom and independence,

and prevailed over his enemy in a series of brilliant

victories and by doing so demonstrated irrefutably that in

Africa there is a black race that can stand on its own and has

all the qualities needed for independent existence."

But

removal of danger from the east did not at all indicate a

weakening of the danger looming on the south and south-west.

The implementation of the claims of England could have

far-reaching consequences, as the actual conditions showed,

that its appetite was insatiable, and historical experience

attested how

multifaceted and dangerous were the means that it used for its

gratification.

Already

in 1899 Menelik stopped all hostile act against the Sudan,

which was temporarily striving for independence under the

Mahdi, correctly thinking that he should not distract the

Mahdi from his struggle with the English, and by so doing

scatter his forces which were necessary for repulsing the

enemy that was more dangerous at that time -- Italy, which by

all means strove to make Ethiopia clash with the Sudan.(19) In

th victory of the Mahdi, the Negus rightly perceived a

guarantee that Europeans would not penetrate to his own

land,(20) for to him it was quite clear that, having seized

Khartoum and Omdurman, the English would advance on Ethiopia;

and, moreover, it was possible, they would not hestiate to use

armed force.(21)

In

the Sudan, from the Egyption border to Khartoum, slowly but

steadily advanced the twenty-thousand-man corps of General

Kichener. From the south, from Uganda, he was supposed to be

joined by the detachment of Major MacDonald, who had been

ordered to take possession of the upper reaches of the Nile,

the Jubba River, and the mouth of the Omo River, flowing into

the recetnly discovered Lake Rudolph. This way, the English

would have seized not only all the land adjacent to the upper

and middle reaches of the Nile, but also regions directly

bordering on Ethiopia.

However,

these plans were not realized, and not only because

MacDonald's soldiers mutinied. The possible strengthening of

England in this region did not at all please the French, who

for a long time had been rivals with England in Africa. The

Sudan, in the opinion of the French government, ought to

recognize the possessions of Turkey, to turn over the eastern

part of the Equatorial Province to Ethiopia, "confirming its

right to independent existence," and to annex the western part

of that province to the French Congo.Thus the southern

possessions of England in Africa would have been cut off from

the northern possessions.(22) Taking into account that given

the then existing arrangement of forces in Africa, there was

nothing more the French could succeed in taking in hand, which

was subsequently confirmed by the famous, not at all pleasant

for French prestige Fahsoda Incident. They preferred to have

as their neighbor the Ethiopian and not the British lion.

Therefore, the French representative to the court of Menelik

II let him know that France would not at all be displeased if

he extended the boundaries of his possessions even as far as

the Belgian Congo.

But

Menelik did not need hints, encouragement or incitements. A

wise and far-sighted ruler, he already for a long time

followed with alarm the intrigues of the colonial powers and

how they gradually enslaved free tribes and peoples. Already

in 1891 the Negus very firmly and determinedly expressed that

he would not stay a detached and passive observer, if European

colonial powers began to divide among themselves lands that

had never belonged to Ethiopia. Menelik decided to restore the

old boundaries of his coutnry on the west and the south --

right up to the right bank of the White Nile and Lake

Victoria. It was evident that if he let the English have

freedom of action in this region, he would by so doing put at

risk the independence of his native land.

Advancing

the boundaries of his country to the Congo and to French

possessions, Menelik would forever frustrate their plans to

merge Uganda and the Sudan. Victory over Italy on the one side

and the real threat on the wes in consequence of the

activation of military operations in the Sudan and on the

other side precipiated Menelik's decision to go from words to

action. He began with annexing to Ethiopia states that

bordered his to the south, lands of the Galla, Konta, Kulo and

a series of other tribes. But there were other reasons

determining this decision.

In

case of success, the Abyssinian plateau would be the only

administrative and economic entity that answered the

geographic, natural and ethnic conditions.

Also, do not forget that Ethiopia was a typical feudal state;

and in a feudal environment, wars and the attendent spoils of

the conquerors were the usual means for filling ahe state

coffers and the vital source of feudal enrichment. Rumors of

the fabulous wealth of Kaffa and the incalculable treasures of

its king kindled their imagination and greed. Besides,

territorial concessions to England could ruin Menelik's

prestige in the eyes of his vassals, who recognized the power

of the Ethiopian emperor only so long as they felt his

strength.(23) Beginning in 1881, the predecessors of Menelik

and he himself tried seven times to conquer Kaffa, wanting to

establish their rule over it and to obtain payment of tribute.

But those attempts were unsuccessful.

The

situation changed abruptly after the victory of Ethiopia over

Italy, when excellent weapons fell into the hands of the

Ethiopians. Two thirds of the members of Menelik's army were

armed with rifles, while Kaffa had altogether only three

hundred old guns. You should keep in mind that the Negus,

animated with success and urged forward by the impending

threat from the side of the colonial powers, acted boldly and

decisively.

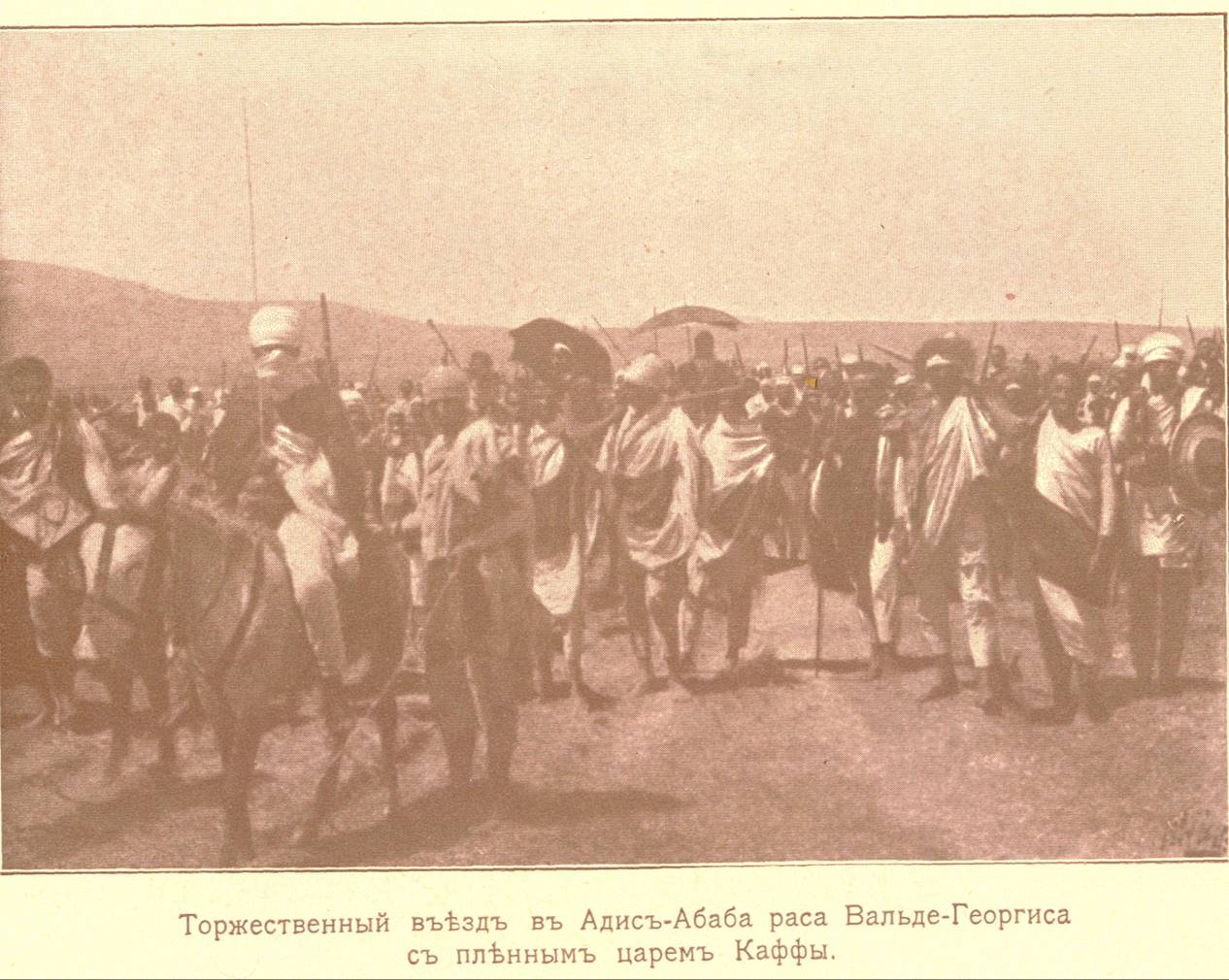

At

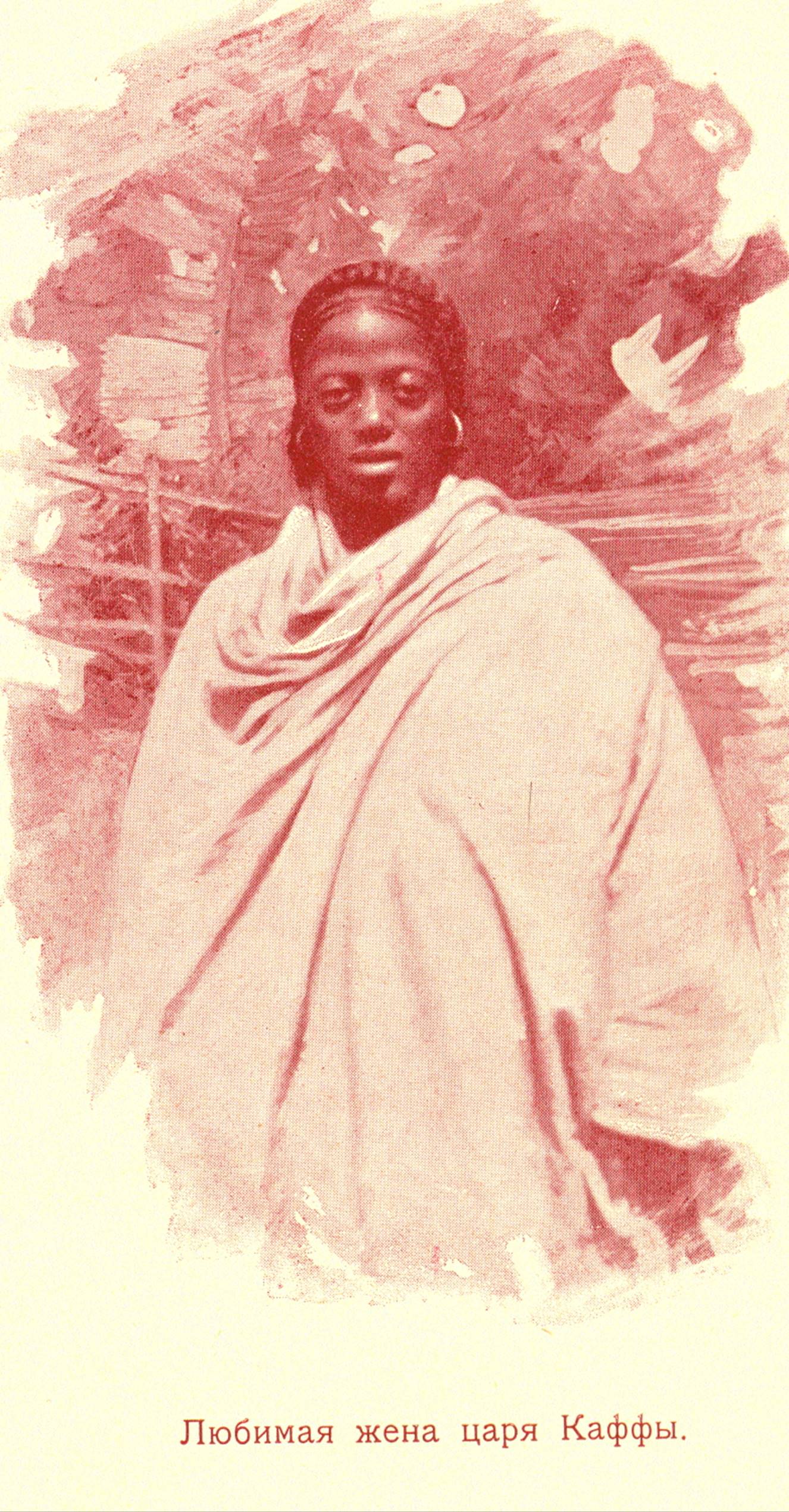

first Menelik intended to annex Kaffa as a vassal state, so

its king, Gaki Sherocho, would keep his rights and

prerogatives. However, the long and fierce resistance of the

poulation, extending the war for seven months -- from March to

September 1896 -- aroused the fear that the people of Kaffa

would revolt at the first opportunity. Therefore, the Negus

annexed Kaffa to Ethiopia, naming its conqueror, Wolde

Georgis, as its ruler. Gaki Sherocho was separated from the

other prisoners and sent to Addis Ababa, and would not be

allowed to leave there. The country was almost completely

devastated. Thousands of warriors fell in battle, defending

their native land.(24) In Europe these events went completely

unnoticed. Very few geographers, ethnographers and specialists

even knew of the existence of Kaffa. Only the Parisian

newspaper "Le Temps" published a small notice, which included

inaccuracies.(25) A.

K. Bulatovich was the first to describe these events in

detail, as F. Bieber mentioned in his work.(26)

Thus

vanished an independent state, which had existed for almost

six centuries. However, from the point of view of the

objective development of the historical process you need to

recognize that in spite of all the brutality permitted the

conquerors, regardless of poverty and hunger which reigned in

Kaffa after the invasion of the armes of the Negus, the

annexation of Kaffa to Ethiopia had a progressive character.

A. K Bulatovich clearly realized this: "Striving to expand the

limits of his domain Menelik is only fulfilling the

traditional mission of Ethiopia as the disseminator of culture

and the unifier of all those inhabiting the Ethiopian plateau

and the

neighboring related tribes and only amounted to a new step in

the establishment and development of the power of a black

empire... We

Russians cannot help sympathizing with his intentions, not

only because of political considerations, but also for purely

human reasons. It is well known to what consequences conquests

of wild tribes by Europeans lead. Too great a difference in

the degree of culture between the conquered people and their

conquerors has always led to the enslavement, corruption, and

degeneration of the weaker race. The natives of America

degenerated and have almost ceased to exist. The natives of

India were corrupted and deprived of individuality. The black

tribes of Africa became the slaves of the whites. Clashes

between nations more or less close to one another in culture

bring completely different results. For the Abyssinians, the

Egyptian, Arab, and, finally, European civilization, which

they have gradually adopted, have not been pernicious."

Indeed,

in Kaffa not only did many primitive and barbaric customs and

ceremonies (including even human sacrifice) disappear, but

also possibilities opened for the production of more

up-to-date weapons, for progressive social-economic relations,

characteristic of the vanguard as compared with that of

Ethiopia. Finally, the conquest put an end to centuries-old

isolation and made possible the penetration of western

capital, and in the given concrete circumsances undoubtedly

played a positive role, helping the revival of the economic

life of the country and the rise of more progressive forms of

ownership.

Such

was in general outline the situation in Ethiopia when A. K.

Bulatovich first went there, attached to the Red Cross

mission, which was under orders of the Russian government in

the spring of 1896.(27)

The

struggle which Ethiopia was carrying out for its independence

elicited a lively response in Russia, especially in its

progressive circles. This much was known: the Ethiopian people

fought for their freedom. It is important to keep in mind that

Russians considered Ethiopians to be brothers in faith -- a

circumstance which then had no small significance. The Russian

press greeted the victory at Adwa with rejoicing. But there

were also more prosaic reasons why the Russian government was

ready to provide real help to Ethiopia.

At

the end of the 19th century in Russia pre-political

capitalism, even though not at the pace of Europe or America,

but none the less swiftly was growing into imperialism, --

with all the peculiarities inherent to it: such as striving to

seize markets and sources of raw material, and expansion, and

bitter conflicts with other imperialist powers. In particular,

conflicts with imperialist powers impelled the Russian

government to support Ethiopia in its struggle with Italy, and

even more so in its struggle with England, a long-time and

dangerous rival of Russia in Asia. A strong, independent and

united Ethiopia (28) would limit the free movement of the

English in Africa and would weaken their position on the sea

routes leading to the Suez and the Red Sea. Finally, Ethiopia

representated a potentially vast market for many Russian

goods.(29) Contemporaries knew this well and made no secret of

it: "What is Abyssia to us? Why is it necessary to Russia?...

Remember that it will play an important role for us in the

future in Asia: England is such a serious rival to us there

and so everything relating to England that takes place in

Africa, where in case of indications of future losses in

India, England will hasten to establish a New Empire, trying

to unite under its rule a conglomerate of lands from Capetown

to Cairo." (30)

Therefore,

in the face of menacing danger Menelik, not wihtout reason

counted on help from Russia, the one large European power

which did not recognize the secret 17th article of the Ucciali

Treaty about the approbation of Ethiopia. (31) As for France,

which significantly more sharly and painfully took a political

position in Africa , namely this circumstance regardless of

the support shown it, made the Negus more guarded in relation

to it. It strove not for the well-being of Ethipia, but rather

to cause as much annoyance as possible to its long-time rival

-- England.

In

Russia, a collection of goods was organized to help the sick

and wounded Ethiopian soldiers [from the Battle of Adwa], (32)

and a detachment of the Red Cross was sent. The decision to do

this was made in March 1896, and 100,000 rubles was allocated

for expenses. (33) Aside from the leader -- Major General N.K.

Shvedov -- 61 men joined.

It

is hard to say what directly prompted A. X. Bulatovich to

apply for inclusion in this detachment to which he was

assigned March 26, 1896. (34) One of his fellow travelers,

F.E. Krindach, in a book that was published in two editions

but which is now very rare, Russian Cavalryman in Abyssinia

(second edition, St. Petersburg 1898), "dedicated to the

description of the 350-verst trek, outstanding in difficulty

and brilliant in accomplishment, which was carried out under

the most extraordinary circumstances by Lieutenant A. X.

Bulatovich in April 1896," considered it necessary in the

introduction "first of all to establish the fact that A. X.

Bulatovich was assigned to the detachment at his own request,

as a private person."

A.

X. Bulatovich strove to prepare himself as thoroughly as

possible for the journey. We know about this not only from his

first book, but also from other sources. For instance,

Professor V.V. Bolotov, historian of the early church, a man

with great and deep knowledge in this area, having mastered

many new and ancient eastern languages, including Geez and

Amharic, on March 27, 1986 wrote "... there appeared an

Abyssinian Hierodeacon Gebra Hrystos [Servant of Christ] and

told me that he wanted me to see Hussar Guard Bulatovich who

is going to Abyssinia. It turned out that Bulatovich wanted to

know which grammar and dictionary of the Amharic language to

get..." (35)

Apparently,

his progress was considerable, because a year later when A. X.

Bulatovich had extended his theoretical preparation and

supplemented it with practice, this same V.V. Bolotov reported

to another addressee "... in March there was no one in

Petersburg who knew Amharic better than I did. Now Life-Guard

Kornet A. X. Bulatovich, who has returned from Abyssinia,

speaks and even writes some in this language." (36)

The

trip to Ethiopia turned out to be longer than anticipated, due

to obstacles put in their way by Italians who hadn't given up

hope of consolidating their position in Ethiopia. Naturally,

any help to Ethiopia, even medical, was undesirable to them.

In

any case, the detachment was not only denied entrance to the

port at Massawa, despite previously obtained permission, but a

cruiser was even dispatched to keep watch on the steamer with

the Russian doctors. (37) Therefore, N.K. Shvedov and his

companions sailed from Alexandria to Djibouti, where they

arrived on April 18, 1896, as indicated in the book written by

F.E. Krindach, who we now let tell the story, since Bulatovich

himself doesn't mention anywhere the events of the first days

of his stay in Africa.

While

the caravan was being formed, the state of affairs (38) made

it necessary to send ahead to Harar an energetic, reliable

person, in view of the fact that the rainy season was rapidly

approaching. One of the prerequisites for successfully

completing this mission was to travel as fast as possible. To

carry out this difficult and dangerous mission, they asked for

a volunteer. Kornet (now Lieutenant) A. X. Bulatovich accepted

the offer. The small Djibouti settlement buzzed with the most

diverse rumors and speculation relating to the possible

outcome of undertaking such a journey, which would be immense

for a European. Not knowing the language and the local

conditions, being totally unprepared from this method of

travel -- on camelback -- and the change of climate -- all

this justified the skepticism of the local residents, the

majority of whom did not admit the possibility of a successful

outcome. It is 350-370 versts [233-247 miles] from Djibouti to

Harar. Almost the whole extent of the route runs along very

mountainous and, in part, arid desert, and permits only travel

with a pack animal. (39)

The

decision to dispatch A. X. Bulatovich as a courier was finally

made on April 21. Taking a minimal quantity of the simplest

provisions and only one water skin of water, A. X. Bulatovich

set out on the route, in spite of the fact that on the way he

could count on only two springs, of which one was hot and

mineral.

On

that very day, April 21, at 10 in the evening, A. X.

Bulatovich, accompanied by two guides, left Djibouti. Even

though he had only had a few hours to practice riding on "the

ship of the desert," on the first leg of the journey he went

for 20 hours without stopping. By the end of the following

day, they had covered 100 kilometers. It is impossible here to

describe all the troubles of this fatiguing and monotonous

journey. The distance of greater than 350 versts [233 miles]

A. X. Bulatovich managed in three days and 18 hours, in other

words about 6-18 hours faster than professional native

couriers. (40) In the course of 90 hours spent on the road,

the travelers rested no more than 14. No European up until A.

X. Bulatovich ever achieved such brilliant results. This trek

"made an enormous impression on the inhabitants of Ethiopia.

Bulatovich became a legendary figure. The author [that is F.E.

Krindach] had occasion to hear enthusiastic accounts of this

trek." (41)

However,

Alexander Xavierevich couldn't stay long in Harar. The

detachment, having arrived after him, intended to continue on

the way farther to Entotto when orders came from the Negus to

wait. Since the rainy season was approaching, which threatened

many complications to making further progress, N.K. Shvedov

decided once again to send A. X. Bulatovich ahead, so he could

in person explain the situation and have Menelik change his

order."The immense crossing from Harar to Entotto, about 700

versts [466 miles], despite the difficulty of the route,

Bulatovich accomplished in eight days. It turned out that

Abyssinians, accustomed to Europeans who came to Abyssinia for

the most part chasing after personal profit, couldn't

understand the unselfish purpose of this detachment.

Therefore, several rases were opposed to the arrival of our

detachment in Entotto. Bulatovich's explanation not only

convinced Menelik to expedite the permission, but even

inspired him with impatience for the rapid arrival of the

detachment. ... On July 12 the detachment reached the

residence of the Negus and was met by Bulatovich..." (42)

The

completion of this mission nearly cost Bulatovich his life.

The road from Harrar to Entotto went through the Danakil

Desert. The small caravan (Bulatovich was accompanied by seven

or eight men) was set upon by a band of Danakil bandits who

took all their supplies and mules. By chance, on June 2, 1896,

they were met by N.S. Leontiev, (43) who was going from

Entotto to Harrar. This was the first meeting of two Russian

travelers in Africa. Judging by the words of N.S. Leontiev's

apologist Yu. L. Yelts, Leontiev furnished A. X. Bulatovich

with all necessities and gave him letters of recommendation to

Frenchmen who were living in Entotto in the service of

Menelik. (44)

A

description of the work of the Red Cross Detachment is a

separate subject which has been sufficiently covered in works

and publications which were sited above, and in the stories of

individuals who were members of it. (45)

Even

several Englishmen, who were forced to accept the presence of

Russians in Ethiopia, couldn't help but note that the mission

sent to them rendered "unselfishly and with good will" help to

the wounded. (46) At the end of October 1896, the detachment

curtailed its work and in the first days of January of the

following year, they returned to Petersburg. As for A. X.

Bulatovich, through N.K. Shvedov, he submitted an application

for an excursion "for a better understanding of the

circumstances in Abyssinia at the time the Red Cross

Detachment left the country" and permission to carry out a

journey to little known and unknown regions of western

Ethiopia. He also wanted to go into Kaffa, which was living

out its last days of independent existence.(47) This request

was supported by the Chief of the Asiatic Bureau Chief of

Staff Lieutenant General A. P. Protseko, who noted the energy

of A. X. Bulatovich in striving to as much as possible become

better acquainted with the country, and his knowledge of their

language and also that the information collected would be very

helpful for the further development of relations with

Ethiopia.

Menelik

categorically forbade crossing the borders of his realm, since

this would mean unavoidable death for the traveler. (48) On

Oct. 28, 1986 A. X. Bulatovich was received by the Negus.

Having obtained all necessary permissions, on the following

day he left the capital and with his fellow travelers set out

for the River Baro. (49) This expedition lasted three months.

He returned on Feb. 1, 1987 and then just two weeks later on

Feb. 13 again set out on a trip, this time to Lekemti, and

then to Handek -- a region in the middle course of the River

Angar and its left tributaries and of the valley of the River

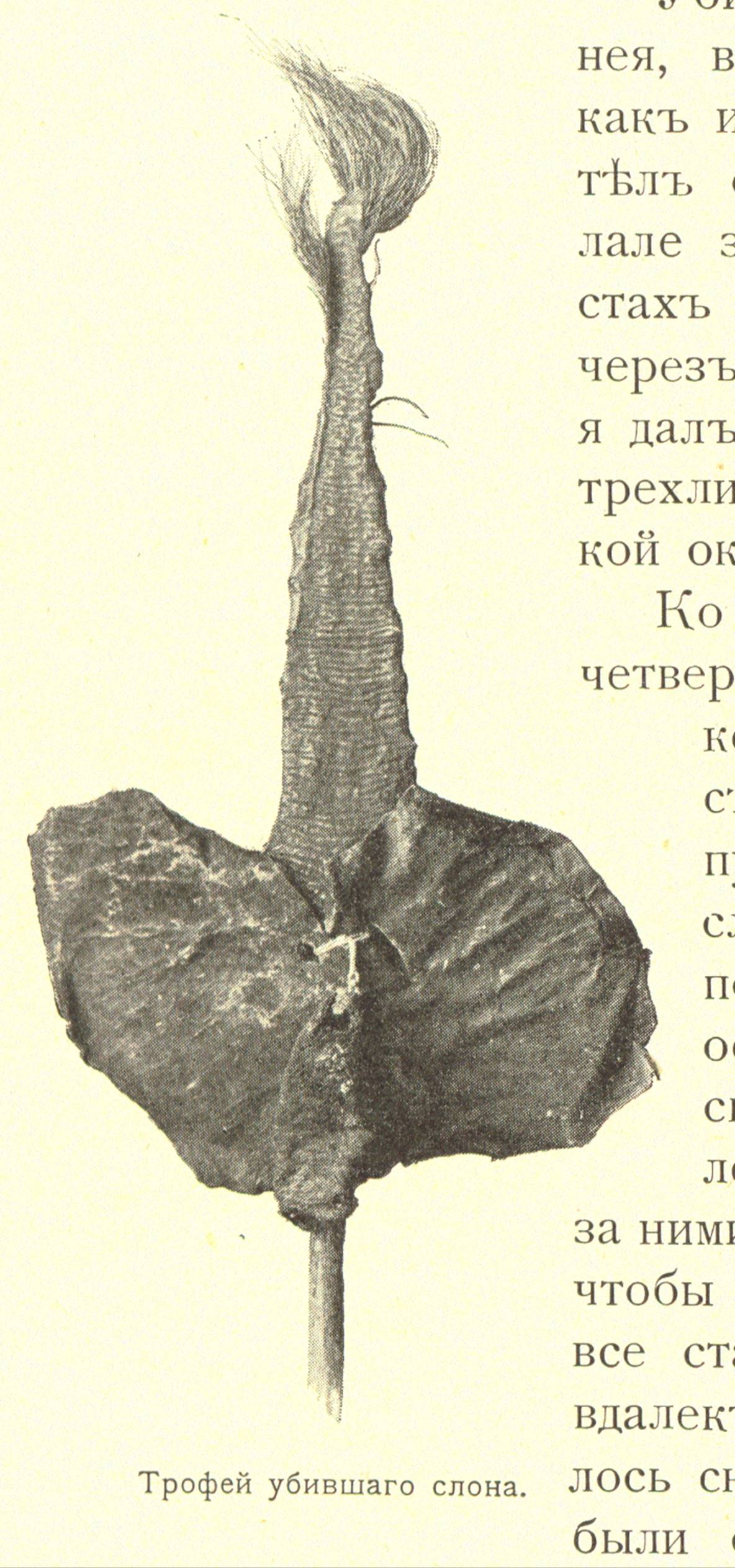

Didessa. Here A. X. Bulatovich took part in an elephant hunt

and occupied himself with learning about the country, its

people and the natural conditions. On his return on March 27,

1897, there was prepared for him a ceremonial reception at the

residence of the Negus, who on the following day gave him a

private audience. Leaving the capital on March 25, A. X.

Bulatovich arrived at Harar on April 4, in Djibouti on April

16, from where on April 21 he sailed to Europe.

On

December 6, 1896, A. X. Bulatovich was promoted to lieutenant

with seniority dating back to August 4, (50) and for help of

the Red Cross Detachment; and for his successful expedition he

was awarded the Order of Anna in the third degree. (51)

The

material he had gathered in the time of his trip, he put into

the form of a book, entitled From Entotto to the River

Baro. An account of a journey in north-western

regions of the Ethiopian Empire and published it on

orders of the General Staff. (52) It appeared in September of

that same year 1897. Thus A. X. Bulatovich wrote it in a very

short time.

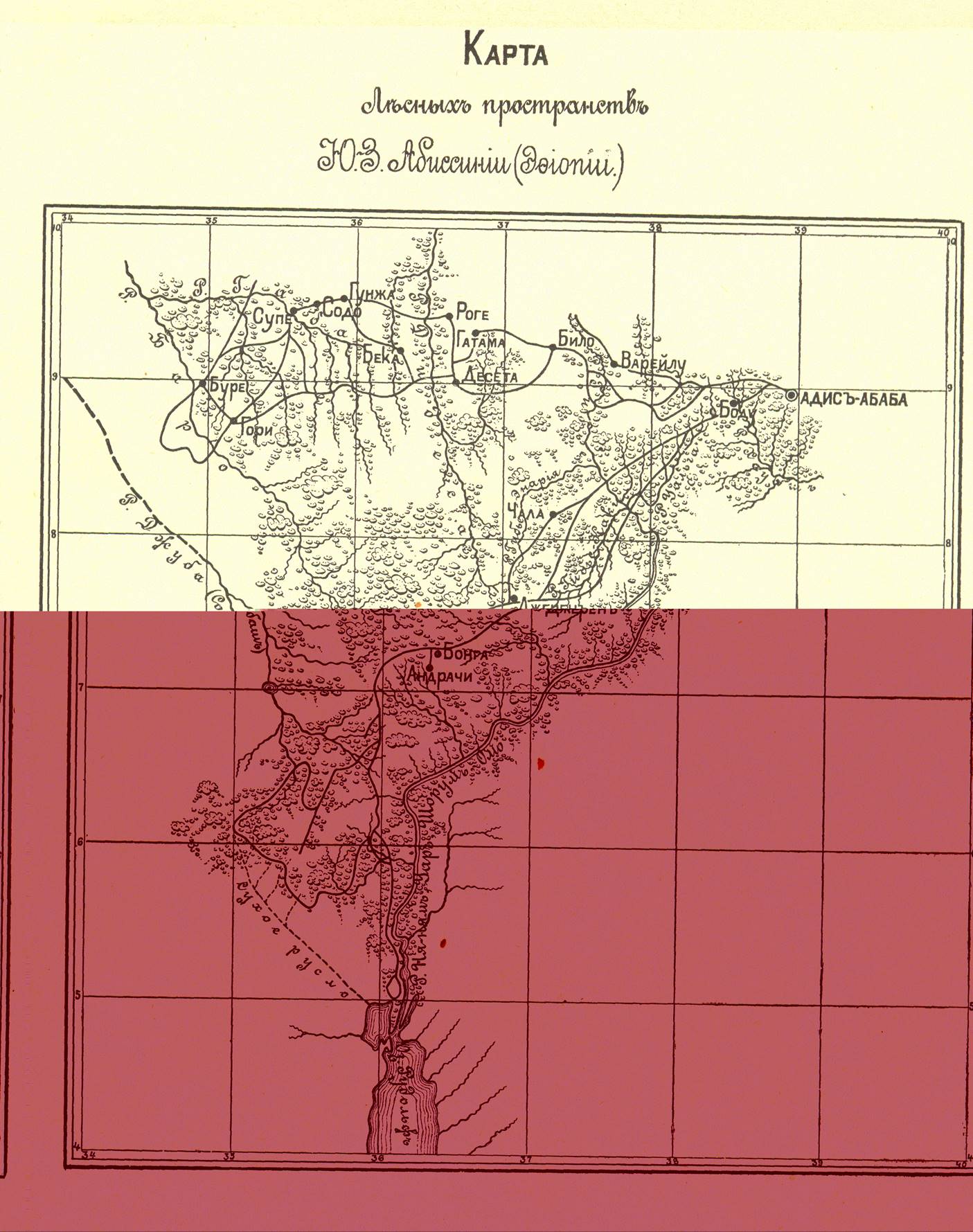

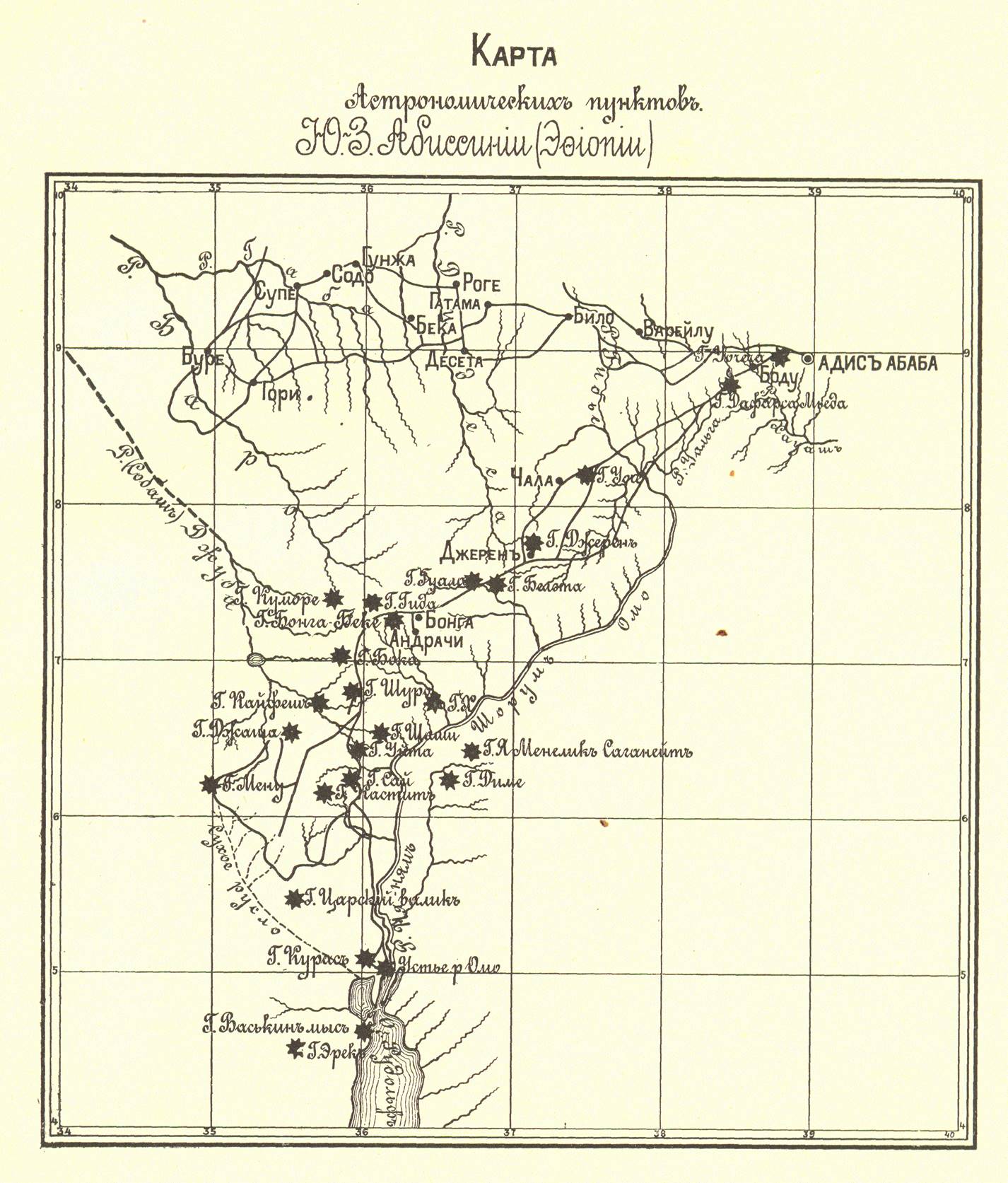

The

region that Bulatovich went through and described lay to the

west of Addis Ababa, roughly between 8 and 10 degrees northern

latitude. The relief of this region of the Abyssinian plateau

was very complex: mountain ranges branching off from the

heights of Kaffa and Shoa alternate with deep river valleys.

These mountain ranges represent the watershed of tributaries

of the Blue Nile, the Sobat, and the Omo.

The

service that Bulatovich performed consisted in the fact that

he was the first to put on the map a significant part of the

river system of the south-western Abyssinian plateau. He

described it and indicated the sources of many riers. Sure, he made

two mistakes: he identified the upper reaches of the Gibye

River with the upper reaches of the Sobat River and thought

that the Baro and Sobat Rivers joined. These errors were

corrected during his second expedition. (53)

The

reader himself can satisfy himself how diverse and instructive

is the information contained in the first book of A. K.

Bulatovich. Of course, not everything he describes is the

result of his own observations; some was gleaned from the

works of other travelers and historians. But many of the facts

brought together by A. K. Bulatovich have have lasting value

for the study of the history and of the way of life of several

peoples of Ethiopia, such as the Galla. He accurately recorded

the formation among them of feudal relationships.

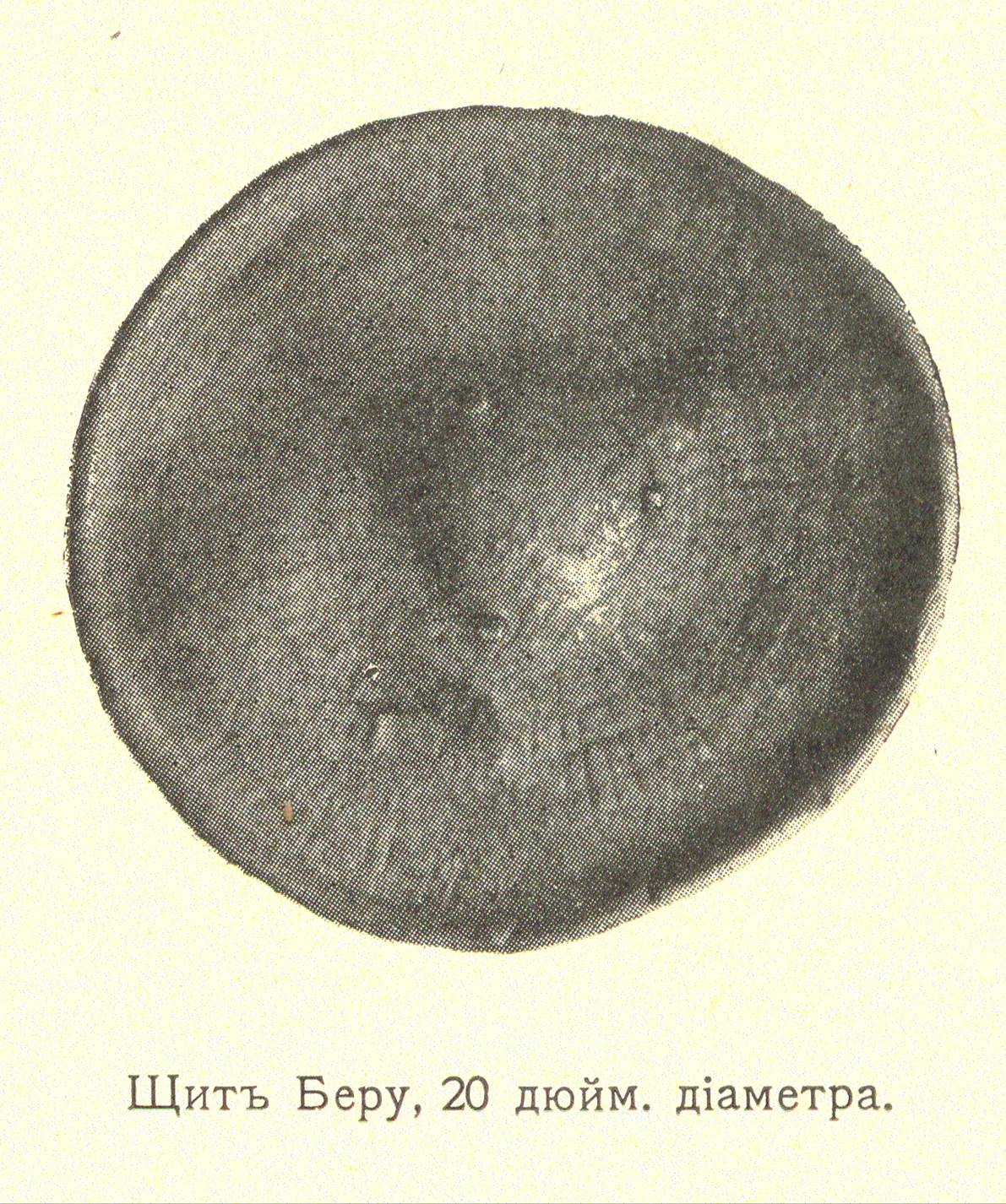

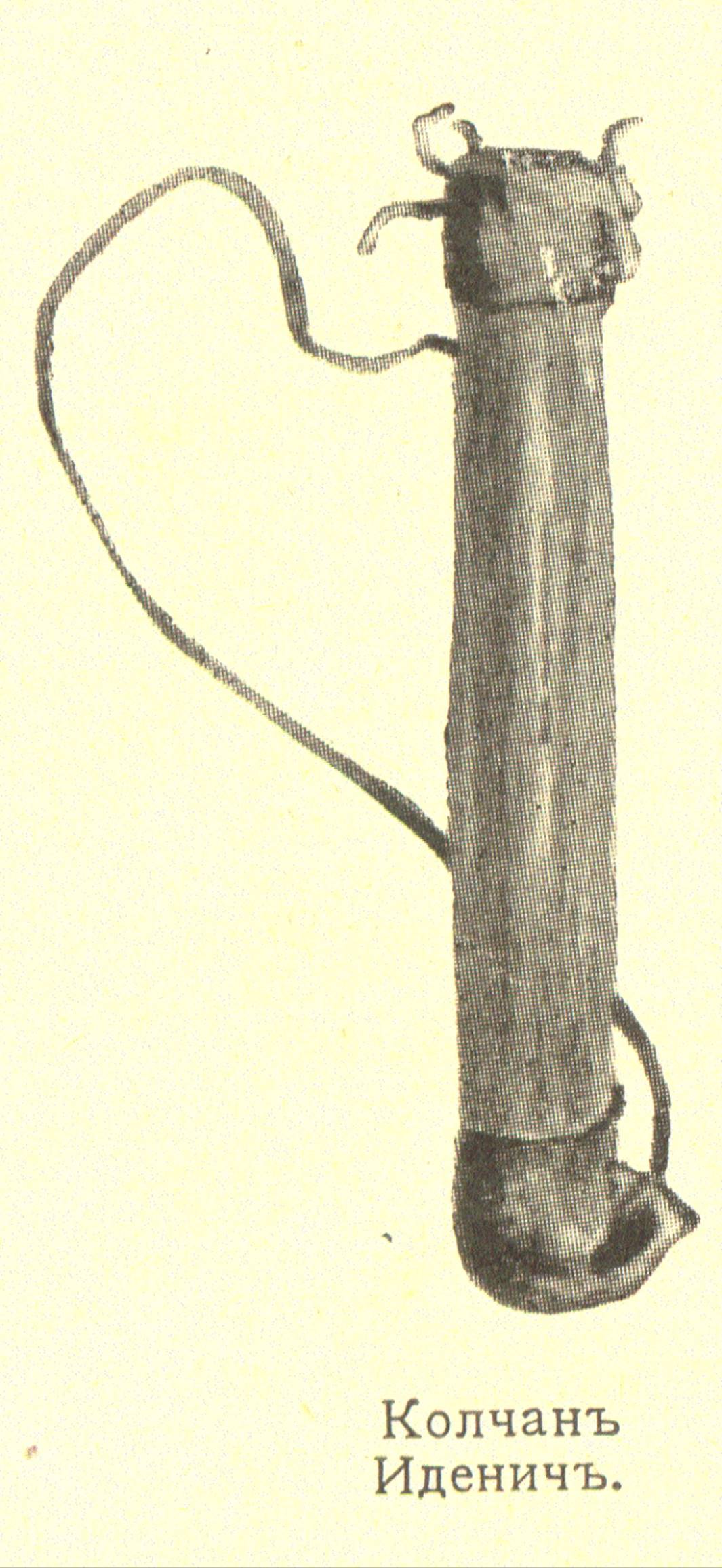

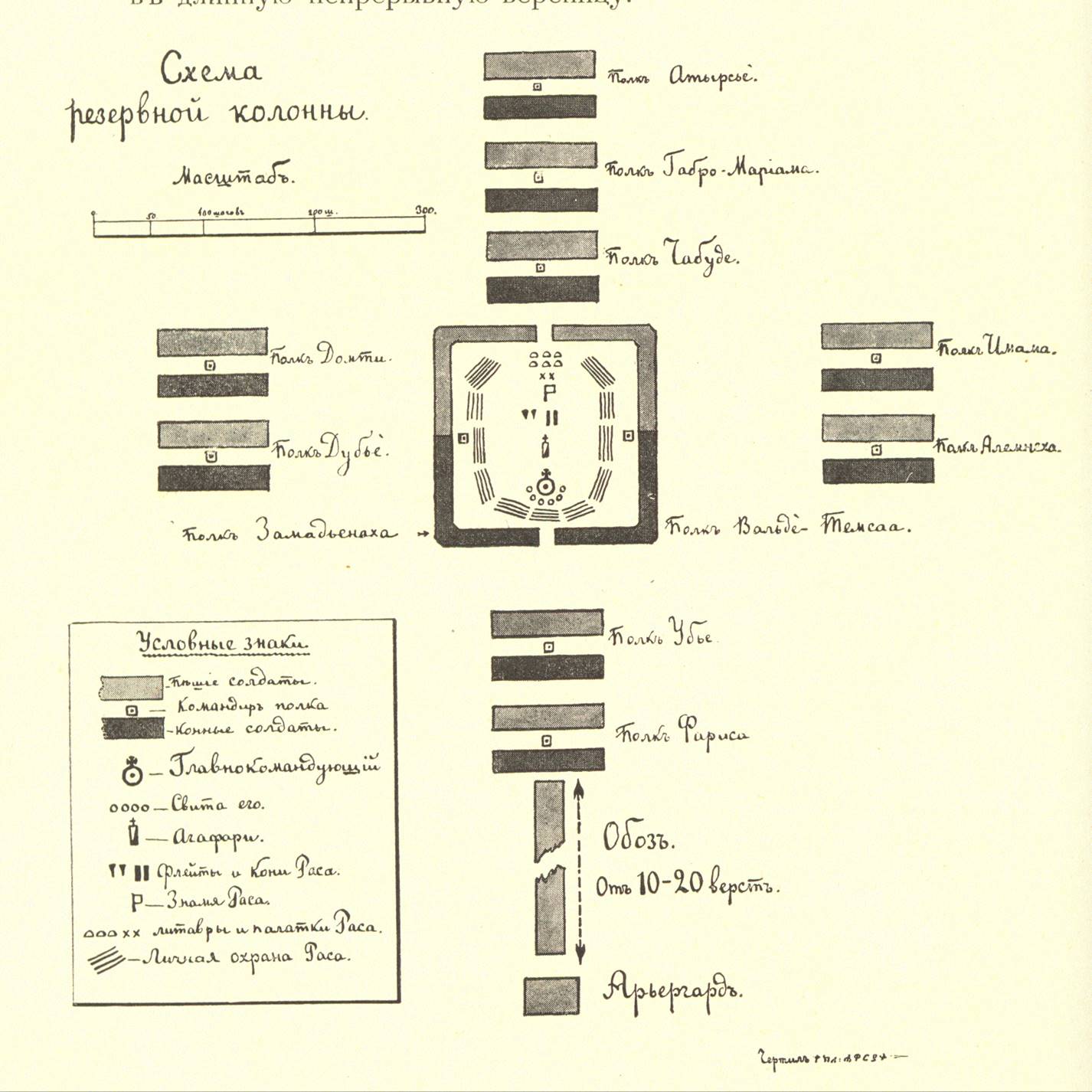

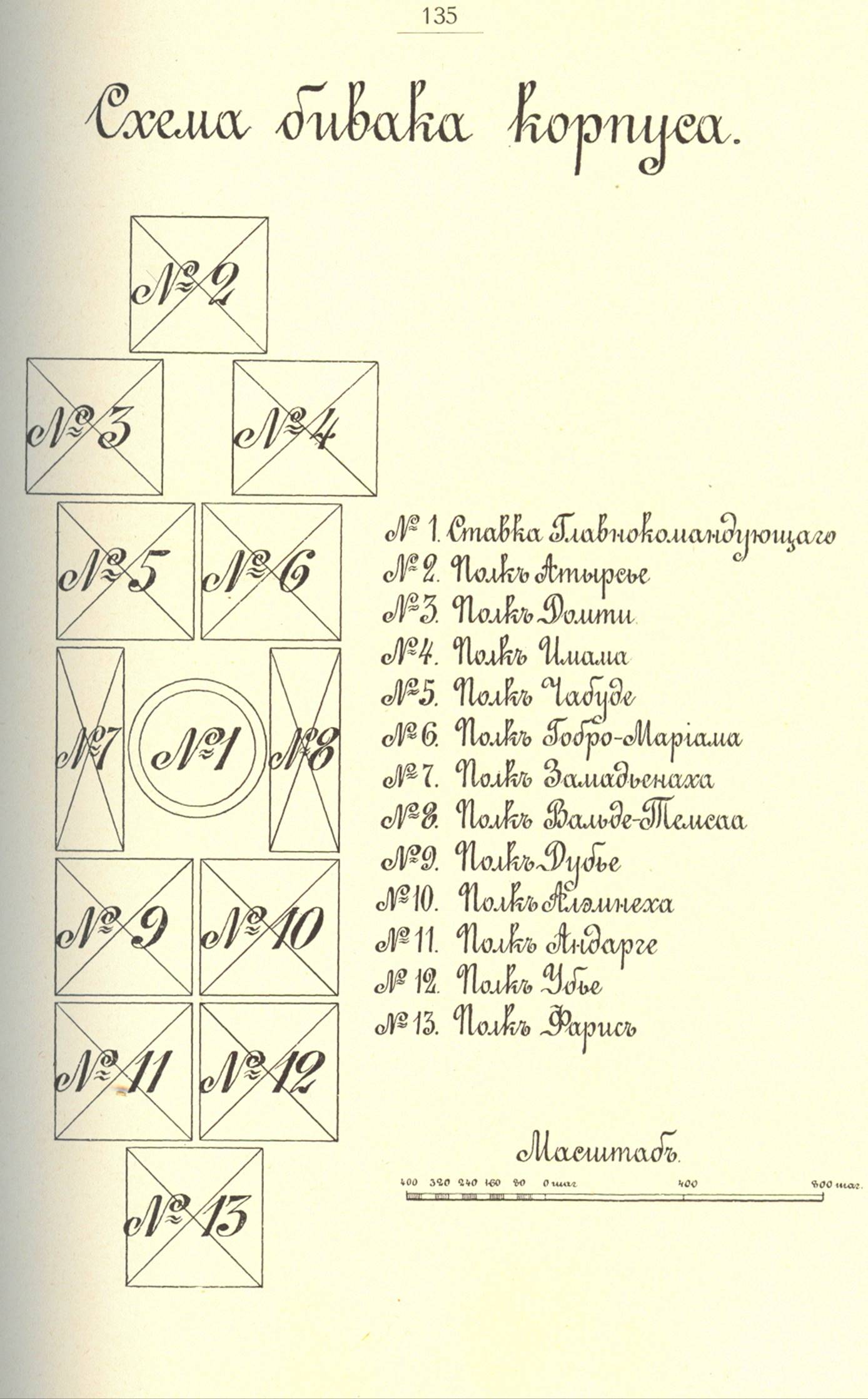

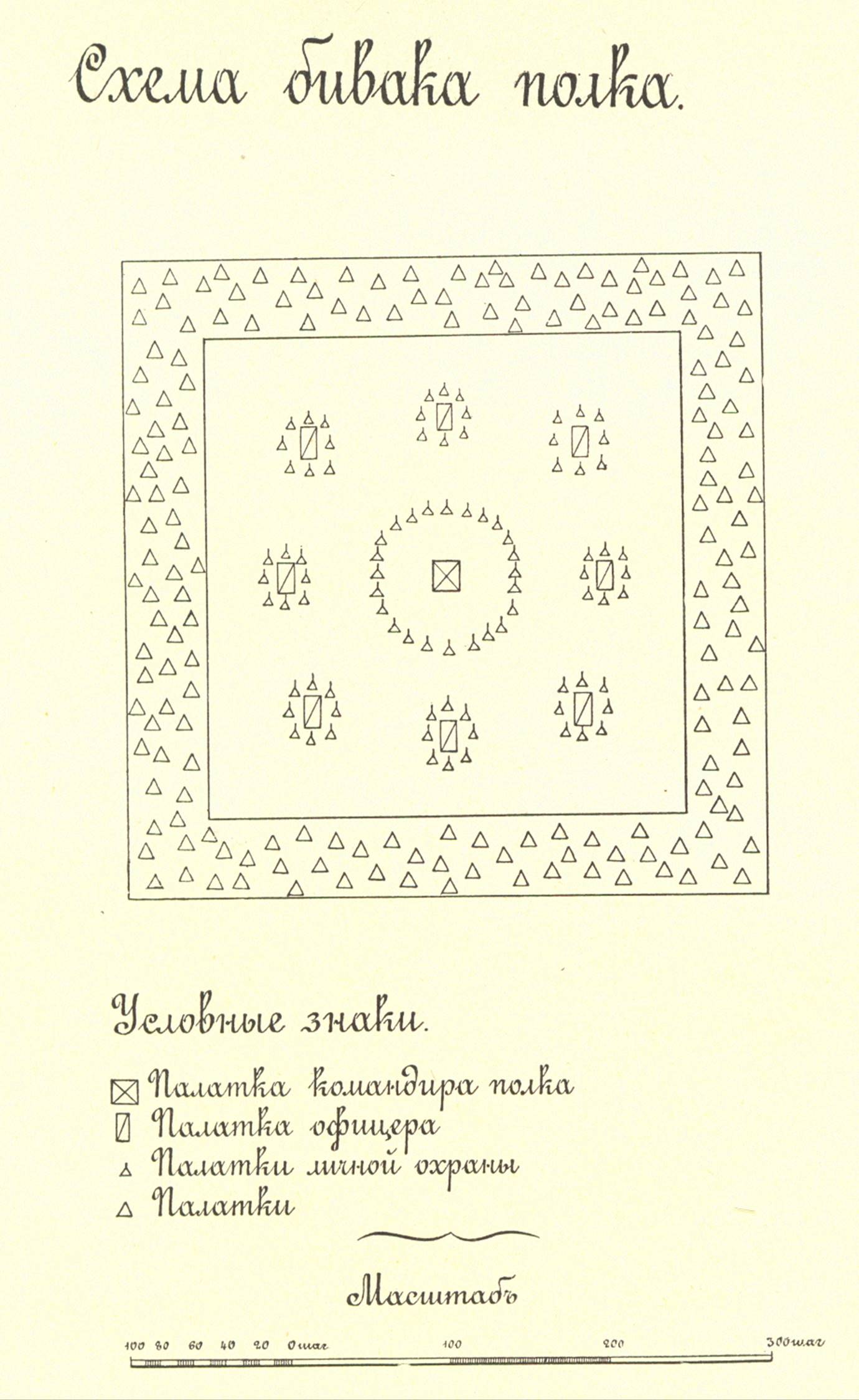

Naturally,

A. K. Bulatovich was interested in the state of the Ethiopian

army. He dedicated a series of pages to military organization,

armaments, and tactics, which given the politics situation at

the time, were, of course, pressingly important. For the

historian, they have not lost interest even today.

For

the publication of A. K. Bulatovich's book, the General Staff

commissioned Colonel S. V. Kozlov to do an analysis of it. This review,

published as a separate brochure, not intended for sale and

now very rare,(54) deserves that we look at it in detail. Reading it, it is

difficult to avoid the impression that this is one-sided

excessively critical and, possibly, the work of a reviewer

with a well-known prejudice, far from just and fair. Setting

aside the evaluation of

what was more current, in other words the personal

observations and discoveries of the author, which the reviewer

only mentions in passing, S. V. Koslov in the most detailed

fashion dwells on the fact that the book of A. K. Bulatovich

by far is not the most important and complete study of the

ancient period of Ethiopian history, on chronological errors,

on mistakes in transcription of Ethiopian words and proper

names, and in these matters, incidentally, the reviewer

himself is far from strong. Blaming the author -- and doing so

energetically -- for ignorance of the literature and for

mistakes on matters that examined

even today are still far from being resolved, such for

instance as the ethnogenesis of the ancient Egyptians,

Ethippians (Cushites), and Semites. S. V. Kozlov himself cited

literature that at his time already was not the last word of

science (G. Ebers, F. Lenorman and others). On the other hand,

S. V. Kozlov left unmentioned serious specialized studies not

that jad beem released not long before and that directly

touched on those questions. (55)

Of

course, A. K. Bulatovich, not having specialized preparation

and not having at his disposal enough free time to deepen his

knowledge in the area of ancient history (he was getting ready

for the next expendition) made some mistakes and inaccurate

definitions, but those should not have been the focus of the

attention of the reviewer. S. V. Kozlov failed to notice what

was most important -- the contribution of the author to the

study of the orography [physical geography dealing with

mountains] of the southwestern part of Ethiopia, several

regions of which he, as already noted, for the first time put

on the map.

Nevertheless,

S. Kozlov in his "Conclusion" admits that "in view of the

personal talents of the author (i.e., A. K. Bulatovich) and

his great power of observation," he managed in a relatively

short time "to gather some interesting information..." (56)

After

the annexation of Kaffa, Menelik did not stop striving to

secure the southern and southwestern boundaries of his

possessions, which, as he declared, included the territory

north of 2 degrees north latitude (now they, in general, do

not extend farther south than 4 degrees north latitude) and

reached to the right bank of the Nile. (57) In order to

strengthen the claim of Ethiopia, the Negus, counting on the

support of Russia and France and hoping that Britan had its

hands tied in its war with the Boers, began to actively

prepare for an expedition to seize disputed regions. Three

armies equipped by him were supposed to set out at the

beginning of 1898.

At

the end of 1897, Russia and Ethiopia reached an agreement for

establishing diplomatic relations. An extraordinary mission,

under the leadership of P. M. Vlasov set out from Petersburg

to Addis Ababa. Attached to this mission, Colonel of the

General Staff L. K. Artamonov was commissioned to compile a

military-statistical descriptionof Ethiopia. (58) The convoy,

consisting mostly of Cossacks, (59) was commanded by A. K.

Bulatovich, aside from whom the staff of the missions only

included a few officers. The head of the Red Cross mission

General Shvedov gave his positive testimonial in a personal

letter to A. P. Protenko. He, by his own acknowlegement, used

for outfitting the military part of the mission "the personal

explanations and reports of Lieutenant Bulatovich." (60)

To

safeguard the reception of the mission and to notify the Negus

of its imminent arrival,A. K. Bulatovich left Petersburg

eearlier than the others -- September 10, 1897. (61) A. K.

Bulatovich was accompanied, at his request, by Private of the

Life-Guard Hussar Regiment Zelepuki, a devoted and courageous

companion who shared with him all the burden and adversity.

(62)

On

his arrrival in Addis Ababa A. K. Bulatovich learned of

Meneliks intention to annex to Ethiopia regions lying to the

north of Lake Rudolph. For that, Ras Waldle Georgis was

setting out for there with his army from the recently

conquered Kaffa. Menelik expressed the desire that the Russian

officer accompany him.

Meanwhile,

the mission of P. M. Vlasov, which set sail from Odessa on

October 19, because of all possible procrastinations and

complications, basically provoked by the malevolence of

colonial European powers, was detained in Djibouti. A. K.

Bulatovich, in order to take part in the expedition to Lake

Rudolph, needed to obtain permission from the head of the

mission whose arrival in the capital had been delayed.

Therefore of his own volition and enterprise Alexander

Xavierevich decided to go to meet the mission, not fearing the

difficult and long, though already known route. But let's

present his own words. Hee is what he wrote on his return to

Adds Ababa on December 26, 1897 to the head of the asiatic

section of the General Staff Lieutenant General A. P.

Protsenko: "The only obstacle... was that I could not go

without the permission of our envoy, and at that time there

was no information about where he wasI had no choice be to go

to meet him as quickly as possible even if I had to go all the

way to Djibouti, which I did. I decided to make this trip on

November 26, by which time I had worked out the plan of the

whole campaign. On November 27 I left for Harar, where I

arrived in six days. The embassy was already in Djibouti. I

stayed in Harar for twenty-four hours, changed men, hiring two

servants, bought two fresh animals and, setting out on the

next day, after four days met the embassy six hours outside of

Djibouti, from which they had already started. This was

December 8. Having stayed with them for two days, on December

10, having taken two fresh mules and three fresh servants, I

started back to Addis Ababa, with the permission of the envoy,

and on December 20, after 10 days, I delivered this letter to

Menelik, who was startled by how quickly I had made the trip

and called me 'a bird.' In 23 days I had gone to Djibouti and

back of which three days were for stop-overs; in other words

in 20 days I went 1600 versts [1060 miles]. Tomorrow, December

27, I should set out to catch up with the army of the ras."

(63) A. K. Bulatovich gave P. M. Vlasov a thorough and rich in

content written

report about the political situation in Abyssinia and the

intrigues of England, Italy, and France. (64)

The

mission after a long and exhausting trip finally arrived on

February 4 1898 in Addis Ababa, where Menelik was impatiently

expecting them, having arranged for the Russian diplomats a

ceremonial reception such as no other embassy had ever been

awarded. (65)

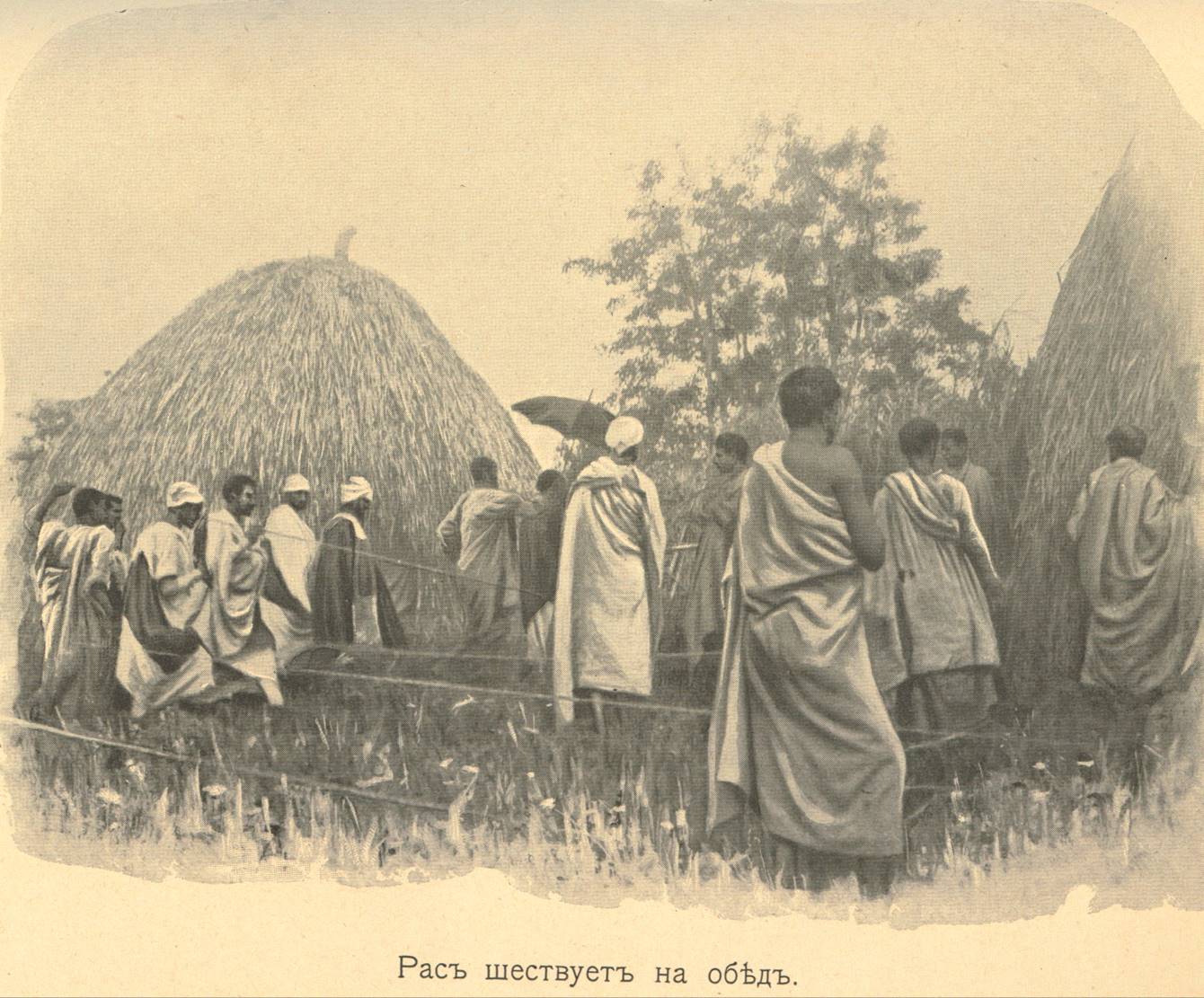

A.

K. Bulatovich really had to move fast: the detachment of Wolde

Georgis was getting ready to set out any day, and to Andrachi

-- the capital of Kaffa -- where the residence of the race was

located, the route was not short, and A. K. Bulatovich, and in

spite of exhaustion, after hisaudience with the Negus he had

to once again get on the road. He tells about this trip in

detail himself, and there is very little left to add to his

narrative. But to understand the importance of the study he

did of Kaffa and of the regions that bordered it to the

southwest, one must briefly take note of what was known about

this country up until the book of A. K. Bulatovich was

published.

The

state of Kaffa arose probably at the end of the 13th century.

It was founded by the Gonga people, which from that time

started to call itself Kaffa. About the ancient history of

this people, the place of their original residence and the

paths they wandered, was saved only by vague legends in the

oral tradition. The king was considered the supreme owner of

all the land and all property and all were his subjects.

Therefore we can say that in Kaffa as in several other

medieval states of Africa there existed an early-class society

with the despotic rule of a deified king, as is characteristic

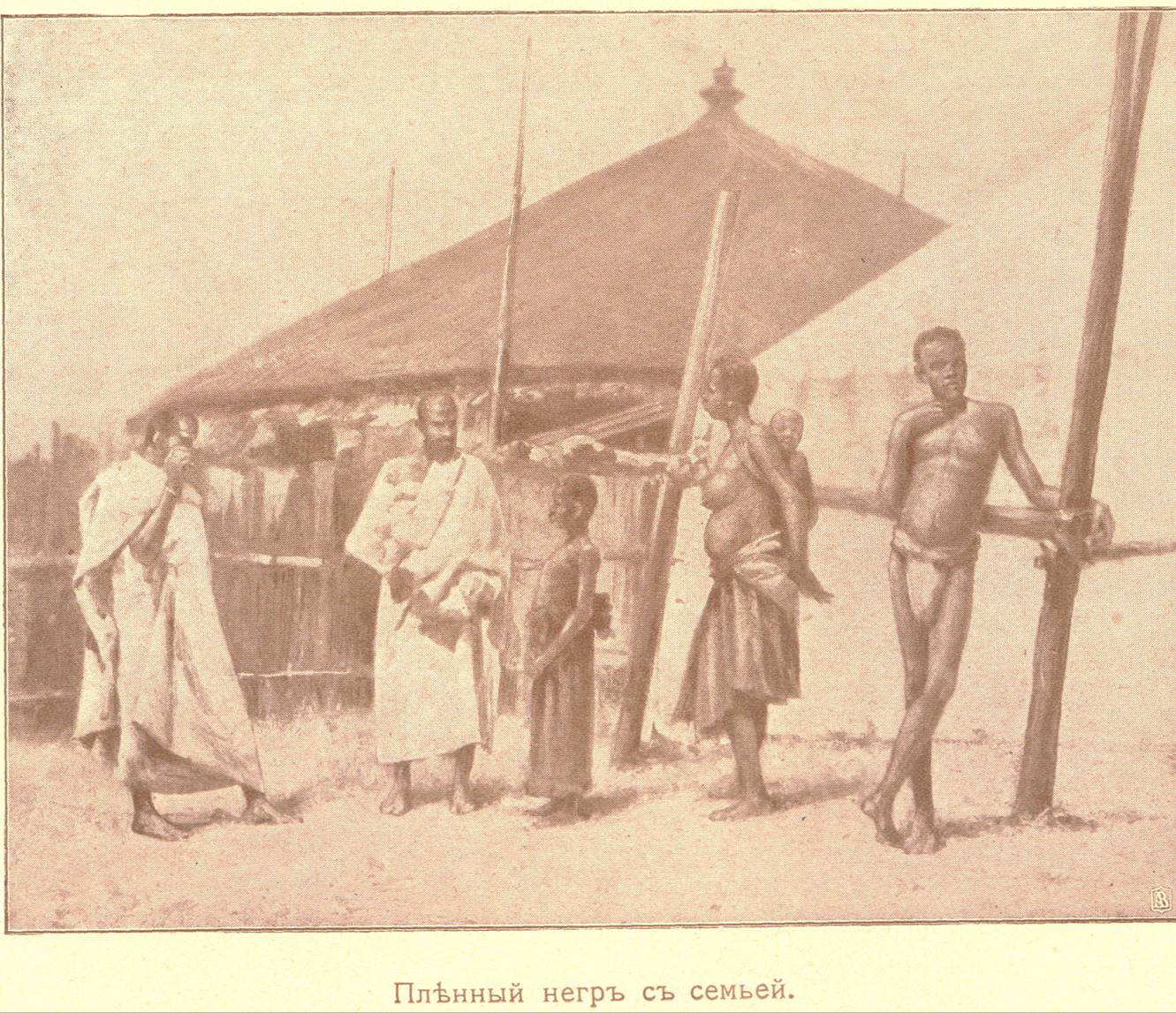

for it. Slavery was relatively wide spread, especially among

the nobility. Rulers and princelings of tribes and

nationalities subdued by the king of Kaffa considered

themselves his vassals and paid a fixed tribute. Not without

the influence of neighboring Ethiopia, they adopted feudal

relationships in the most primitive form .

Striving

to strengthen the existing order, government workers with at

their head the king

and

the council of seven elders --representatiopposed ves of the

most distinguished families (the so-called "mikirecho) -- with

all their strength the penetration of any outside influences.

Trade could only take place in the specially designated for it

city of Bonga, and then only with the permission of the king.

The whole country was surrounded by a fence with watch towers.

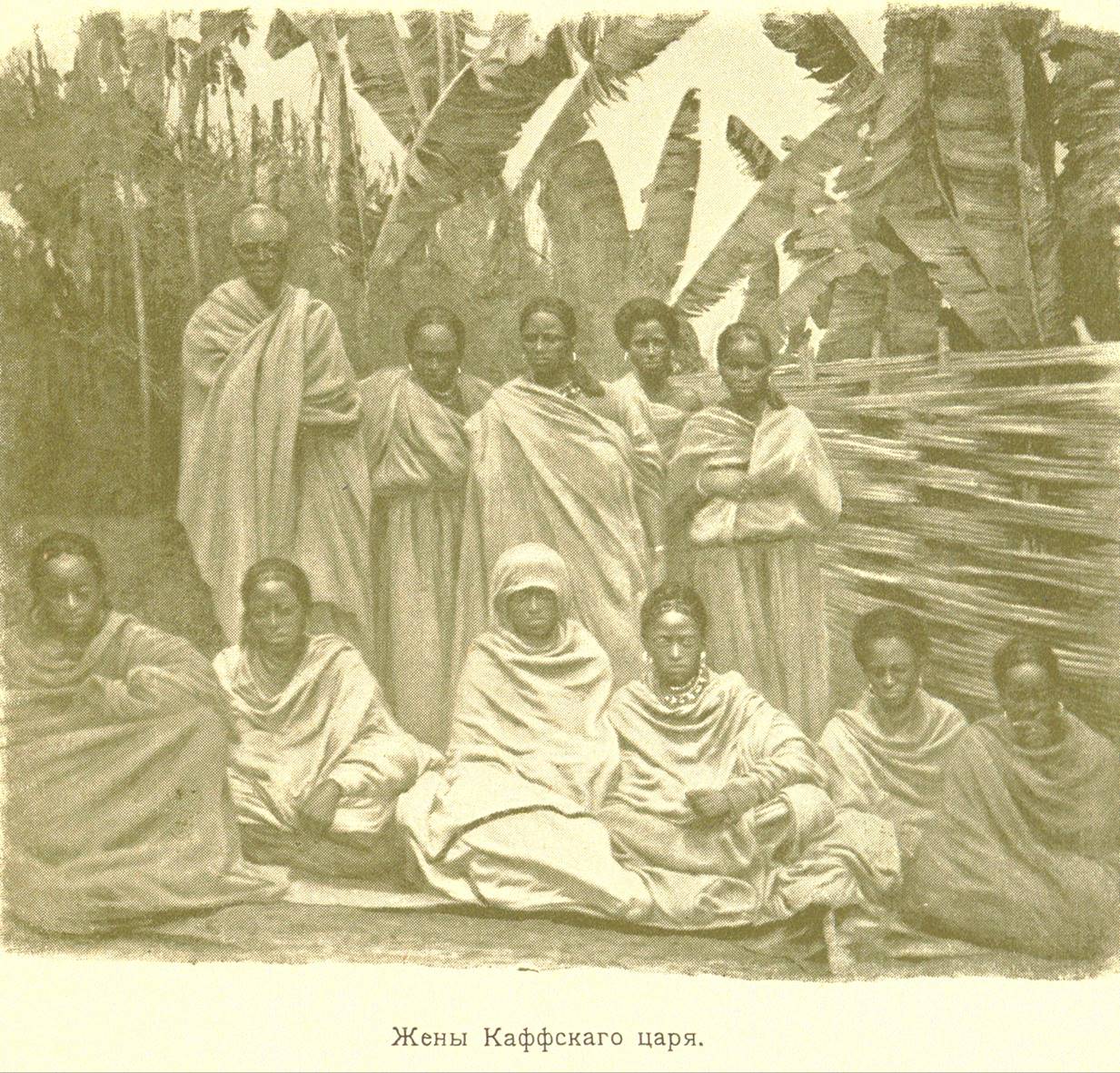

This

is why the first information about Kaffa only reached Europe

in the sixteenth century. In essence, this was only the name

of the capital -- "Cafa."The Portugese Balthasar Tellezwrote

about it in a history of Ethiopia published in 1660.

He used the reports of his compatriot Jesuit missionary Father

Antonio Fernandez, who in 1613 visted lands that neighbored

Kaffa, not going, however to its borders. After that Europeans

forgot about ti. The silence lasted a hundred and thirty

years. At the end of the eighteenth century the well-known

English traveler James Bruce, having found the area of the

sources of the Blue Nile, mentioned Kaffa and described his

travels and reported some details about it.

In

the middle of the nineteenth century the location of Kaffa had

been more or less accurately indicated on maps. The Frenchman

T. Lefevre, who lived for many years in Ethiopia, tried to

reckon up all (but in truth wht amounted to very little) that

was up to that time known about Kaffa, primarily from asking

Ethiopians who had beenthere.

Finally,

in 1843, Antooine d'Abbadie, a prominent French explorer of

Ethiopia, who traveled for 12 years in that country and made

many discoveries about it, crossed the secret borders of

Kaffa. His stay in the forbidden kingdom lasted eleven days,

and he never penetrated beyond Bongo. But in this brief time

he made valuable geodesic observations. In addition, he

gaathered some information about Kaffa during his long travels

in Ethiopia. (66)

For

almost two years (from October 1859 to August 1861) a monk of

the Cappuchin order lived there. He later became Cardinal G.

Massai, the head of a Catholic mission. However, the excessive

zeal they showed in trying to "save the souls" of the local

people prompted the then reigning king to kick Massai out of

the country. After he became cardinal, Massi wrote twelve

volumes about his stay in Ethiopia. Of those only one was

devoted to Kaffa, its inhabitants, and their customs and ways

of life. (67) These writings, done from memory (the journals

of Massai were lost), have significant value, as they tell of

those years when Kaffa had not yet lost its independent.

Capitan

A. Chekki and Engineer Kyarini after an exhausting, very

dangerous journey arrived at the region of Gera to the north

of Kaffa. Here they were detained. With difficulty, combining cleverness

and force, they succeeded in freeing themselves. In June of

1879 they over the course of a week walked through the

northern region of the country and avoiding Bonga, penetrated

yp the region of Kor, which was located to the northwest of

Kaffa. Not able

to endure the difficulties of the trip, Kyarini died in

October of that year. As for A. Chekki, he prublished a

descripton of Kaffa and its inhabitants. The account even

included a grammar of the Kaffa language. (68)

One

of the few Europeans who succeeded in visited this almost

legendary country in the last years before the end of its

independence was the Frenchman P. Soleillet. But his stay in

Kaffa losted only ten days (in the middle of December 1883)

and was limited to just the northern outskirts. Nervertheles,

P. Soleillet was lucky enogh to catch sight of something that

after him no one else saw -- Kaffa in all its ancient

splendor. He published his impressions and observations for

the first time in the journal of the geographic society of

Rouen, and then published a separate book which today is very

rare. (69)

So,

at the end of the nineteenth centruy only five Europpeains had

managed to visit Kaffa: three Italians and two Frenchmen. only

G. Massai could stay there more than two weeks, but no one

managed to penetrate to the depth of the country. They could

only acquaint themselves with the outskirts, primarily the the

northern outskirts.

This

is why A. K. Bualtovich could for good reason call himself

"the first to pass through" Kaffa. It is true that he saw this

amazing country after it was devastated and ravaged, with

wounds that had not yet scarred, inflicted on them by their

conquerors. when they had not yet forgotten the events of war

-- only a few months had passed since the Kaffa were

subjugated by Menelik, but the memories were still vivid of

the old traditions, customs, and the way of life. Therefore,

Bulatovich could gather such information which later

travellers would not be able to because it was no longer in

existence. This is why the material gathered by him is one of

the basic sources of knowledge about the istory and

ethnography of Kaffa.

On

June 5, 1898, Bulatovich returned to Addis Ababa and after

nine days set out by courier to Petersburg, where he stayed

until the end of July.

According

to his words, during the time of his second trip to Ethiopia,

not counting crossings by railroad and steam ship, he covered

about eight thousand versts (5300 miles), over the course of

which there were only four more or less lengthy stops

amounting to a total of 69 days. He was on the go for 211

days, having spent a significant amount of his own money --

about five thousand rubles. (70)

The

reports of Bulatovich, which only partially -- together with

diplomatic considerations -- were represented in the book

"With the Armies of Menelik II," contained very valuable

historical information about the political and military

situation that arose in Ethiopia n the closing years of the

nineteenth century. P. M. Vlasov more than once used those

reports in his communiques to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Not without reason, he wrote there presenting "the full report

of Lieutenant... Bulatovich about his nearly five-month stay

in the southern detachment of the Ethiopian army, with which

he succeeded in going to Lake Rudolph and shared all the

burdens, hardships, and dangers of that journey, undertaken in

completely unknown, and never before discoveredded country...

The said officer... had to deny himself all of the most

necessary things, even including normal food and submited

himself extremely difficult for Europeans regimen. It is

important to give Lieutenant Bulatovich credit: over the

course of this journey he showed himself as a Russian officer

of the best kind, and clearly demonstrated to the Ethiopians,

how capable the valiant Russian army could be, selflessly

devoted to its duty, a brilliant representative of which he

appears among them..." (71).

And

A. K. Bulatovich managed all his commissions, including

diplomatic ones, superbly.When in the spring of 1898, P. M.

Valsov noticed some colling of Menelik toward Russia, not

without basis attrubuted by him to intrigues of some European

advisors (for example, A. Ilg), who were not at all interested

in the strengthening of the influence of Russian diplomats, A.

K. Bulatovich in his next audience with the Negus, using his

knowledge of the Amharic language, in the absence of A. Ilg

cleared up the situation and made certain that this was the

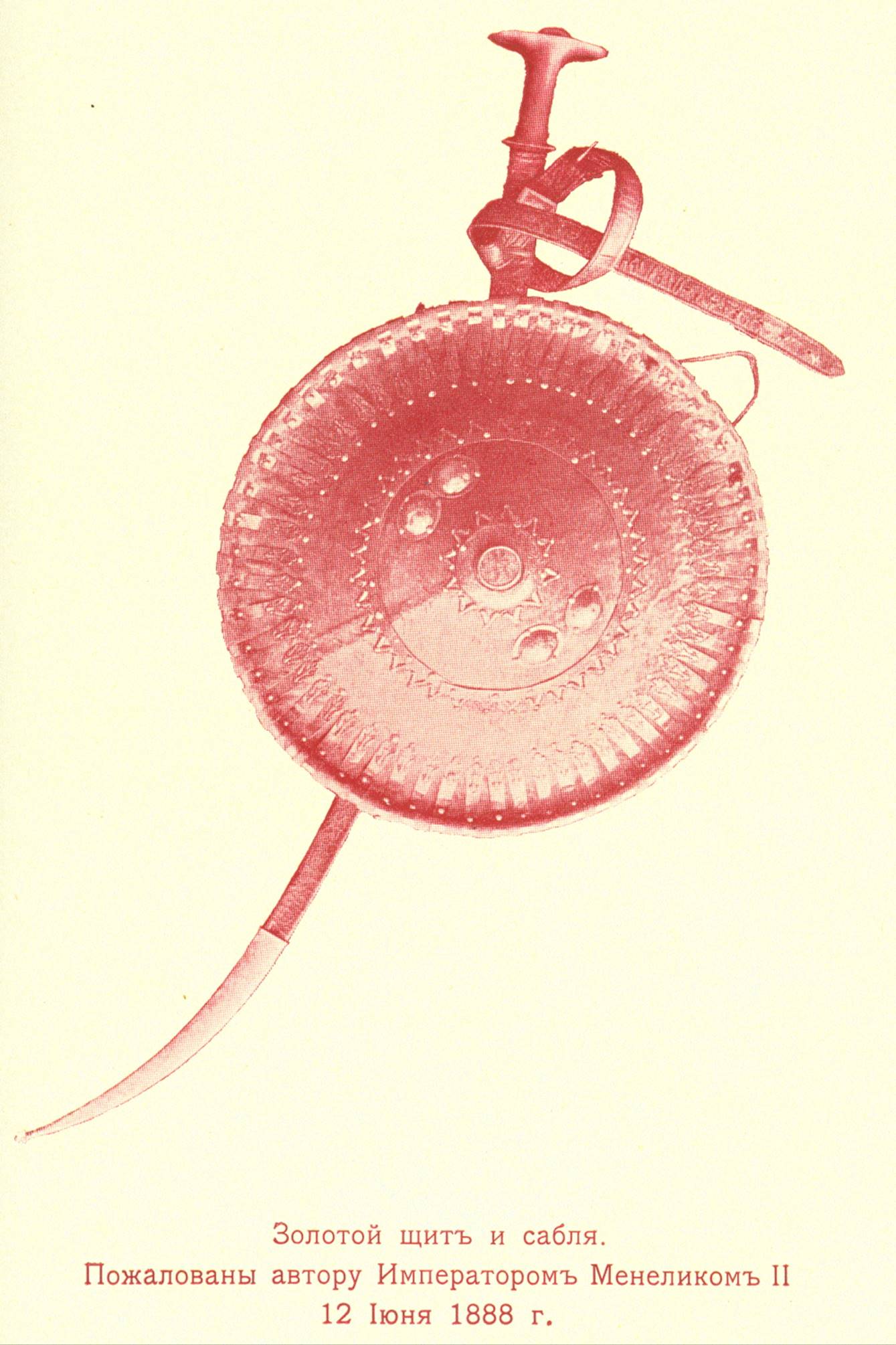

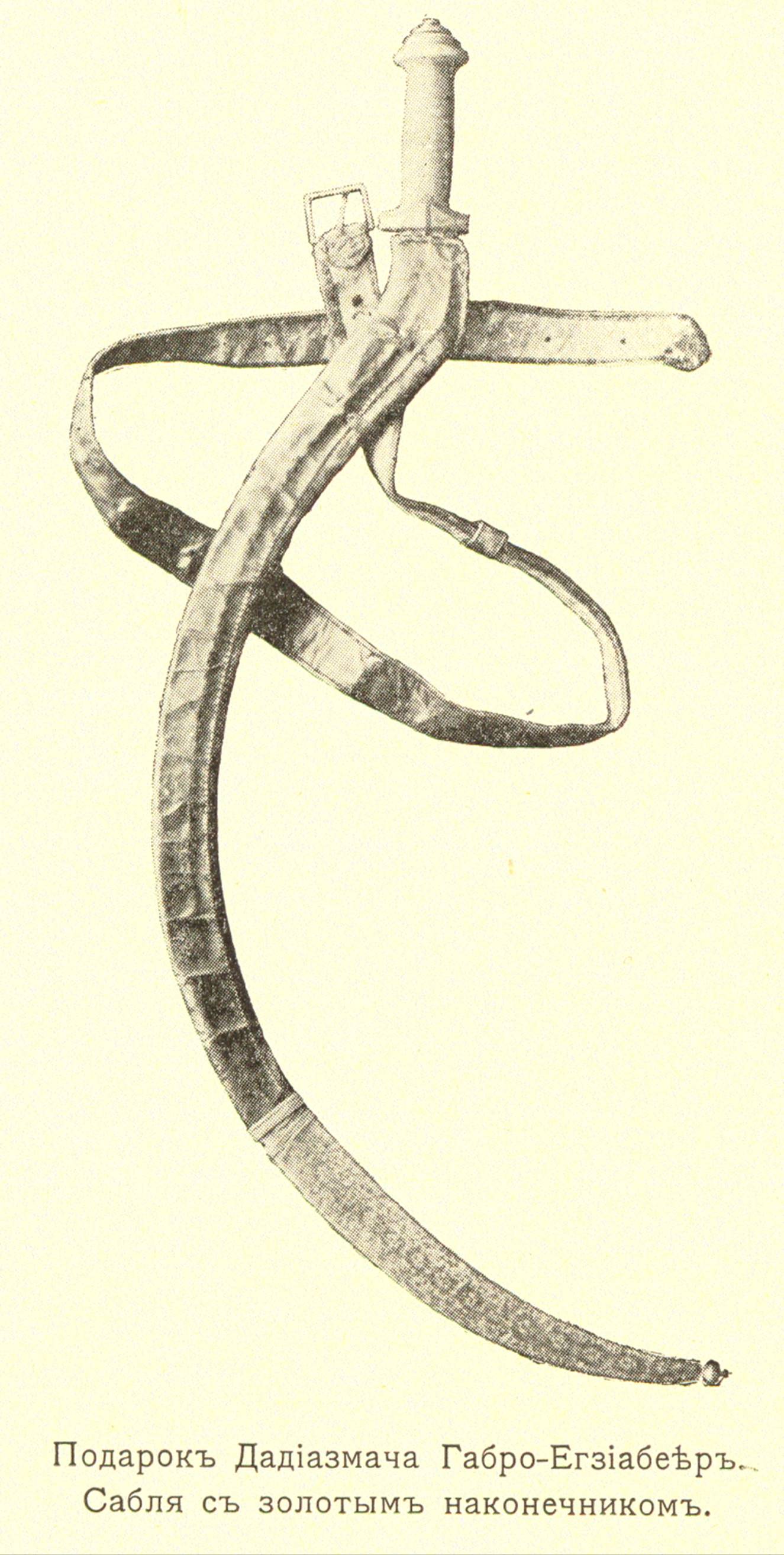

last action of that mission. (72) As testimony to the prowess

of A. K. Bulatovich and his service to Ethiopia ws the highest

military honor -- a golden shield and saber, given to him by

Ras Wolde Georgis, and that was approved by the Negus, who in

an official announcement to P. M. Vlasov on June 14, 1898 said

about the Russian officer: "I sent Alexander Bulatovich to war

with Ras Wolde Georgis. What

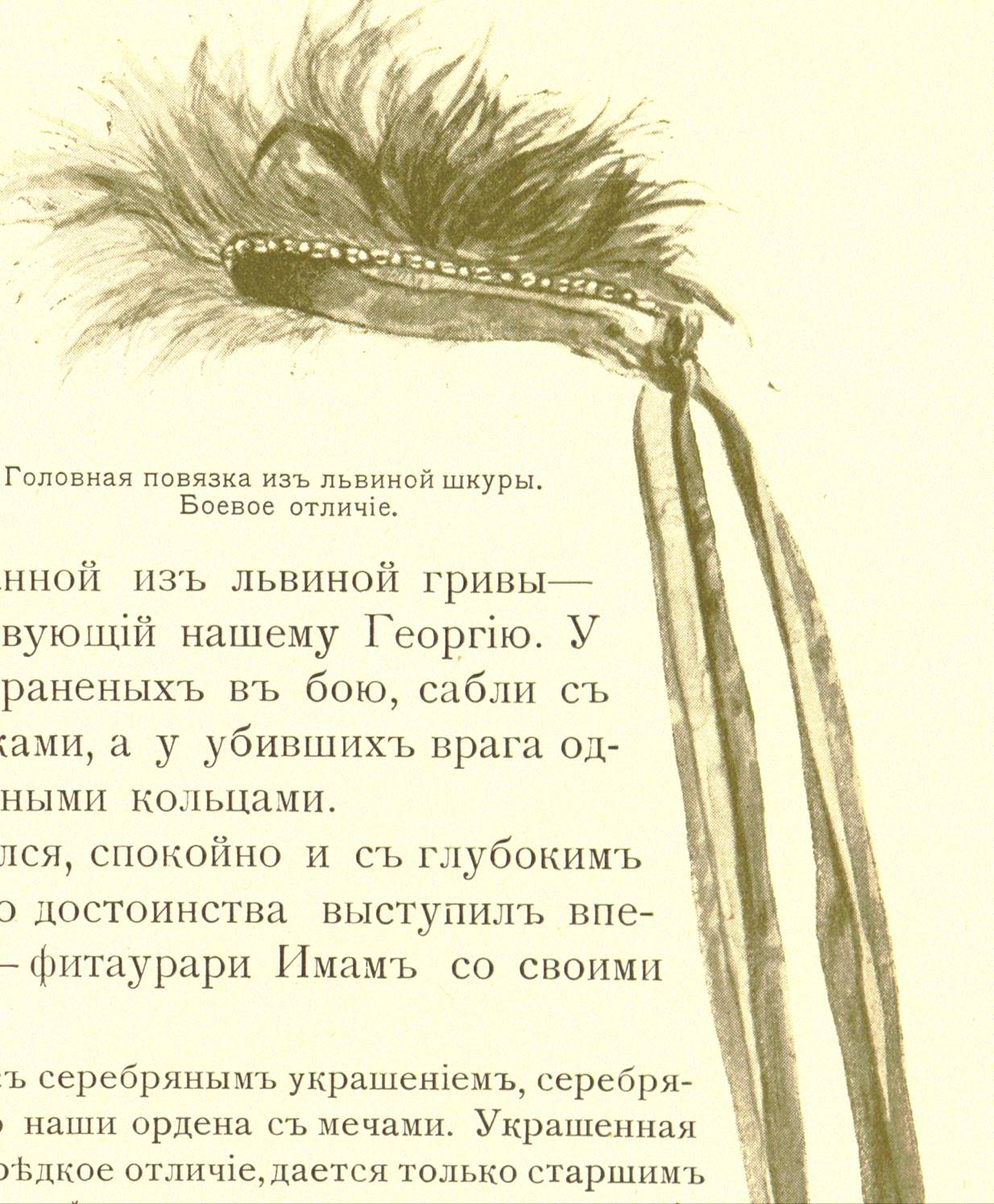

Wolde Georgis wrote to me about his behavior delighted me. The